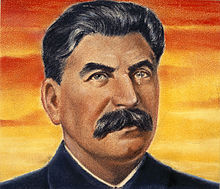

Joseph Stalin or Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin (Russian: Ио́сиф Виссарио́нович Ста́лин, pronounced [ˈjosʲɪf vʲɪsɐˈrʲonəvʲɪt͡ɕ ˈstalʲɪn]; born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jugashvili, Georgian: იოსებ ბესარიონის ძე ჯუღაშვილი, pronounced [iɔsɛb bɛsariɔnis d͡ze d͡ʒuɣaʃvili]; 18 December 1878[1] – 5 March 1953), was the leader of the Soviet Union from the mid-1920s until his death in 1953.

Among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who took part in the Russian Revolution of 1917, Stalin was appointed general secretary of the party's Central Committee in 1922. He subsequentlymanaged to consolidate power following the 1924 death of Lenin through suppressing Lenin's criticisms (in the postscript of his testament) and expanding the functions of his role, all the while eliminating any opposition. By the late 1920s, he was the unchallenged leader of the Soviet Union. He remained general secretary until the post was abolished in 1952, concurrently serving as the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1941 onward.

Under Stalin's rule, the concept of "socialism in one country" became a central tenet of Soviet society. He replaced the New Economic Policy introduced by Lenin in the early 1920s with a highly centralised command economy, launching a period of industrialization and collectivization that resulted in the rapid transformation of the USSR from an agrarian society into an industrial power.[2] However, the economic changes coincided with the imprisonment of millions of people in Soviet correctional labour camps[3] and the deportation of many others to remote areas.[3]The initial upheaval in agriculture disrupted food production and contributed to the catastrophic Soviet famine of 1932–1933, known as the Holodomor in Ukraine. Later, in a period that lasted from 1936–39, Stalin instituted a campaign against alleged enemies within his regime called the Great Purge, in which hundreds of thousands were executed. Major figures in the Communist Party, such as the old Bolsheviks, Leon Trotsky, and several Red Army leaders, were killed after being convicted of plotting to overthrow the government and Stalin.[4] These campaigns were in addition to the existing political repression in the Soviet Union, which was in effect continually after the October Revolution.

In August 1939, Stalin entered into a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany that divided their influence and territory within Eastern Europe, resulting in their invasion of Poland in September of that year, but Germany later violated the agreement and launched a massive invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Despite heavy human and territorial losses, Soviet forces managed to halt the Nazi incursion after the decisive Battles of Moscow and Stalingrad. After defeating the Axis powers on the Eastern Front, the Red Army captured Berlin in May 1945, effectively ending the war in Europe for the Allies.[5][6] The Soviet Union subsequently emerged as one of two recognized world superpowers, the other being the United States.[7] The Yalta and Potsdam conferences established communist governments loyal to the Soviet Union in the Eastern Bloc countries as buffer states, which Stalin deemed necessary in case of another invasion. He also fostered close relations with Mao Zedong in China and Kim Il-sung in North Korea.

Stalin led the Soviet Union through its post-war reconstruction phase, which saw a significant rise in tension with the Western world that would later be known as the Cold War. During this period, the USSR became the second country in the world to successfully develop a nuclear weapon, as well as launching the Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature in response toanother widespread famine and the Great Construction Projects of Communism. In the years following his death, Stalin and his regime have been condemned on numerous occasions, most notably in 1956 when his successor Nikita Khrushchev denounced his legacy and initiated a process of de-Stalinization. He remains a controversial figure today, with many regarding him as a tyrant[8] similar to his wartime enemy Adolf Hitler; however, popular opinion within the Russian Federation is mixed.[9][10][11]

Contents

[show]Early life

Main article: Early life of Joseph Stalin

Stalin was born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili (Georgian: იოსებ ბესარიონის ძე ჯუღაშვილი; Russian: Ио́сиф Виссарио́нович Джугашви́ли, Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili,pronounced [d͡ʐʊɡɐˈʂvʲilʲɪ]) on 18 December 1878[1] in the town of Gori, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Georgia). His mother was Ketevan Geladze. His father Besarion Jughashvili worked as a cobbler.

As a child, Ioseb was plagued with numerous health issues. He was born with two adjoined toes on his left foot.[12] His face was permanently scarred by smallpox at the age of 7. At age 12, he injured his left arm in an accident involving a horse-drawn carriage, rendering it shorter and stiffer than its counterpart.

Ioseb's father slid into alcoholism, which made him abusive to his family and caused his business to fail. When Ioseb's mother enrolled him into an Orthodox priesthood school against her husband's wishes, his enraged father went on a drunken rampage. He was banished from Gori for assaulting its police chief. He subsequently moved to Tiflis (Tbilisi), leaving his family behind.

When Stalin was sixteen, he received a scholarship to attend the Georgian Orthodox Tiflis Spiritual Seminary in Tbilisi. Although his performance had been good, he was expelled in 1899 after missing his final exams. The seminary's records also suggest that he was unable to pay his tuition fees.[13] Around this time, Stalin discovered the writings of Vladimir Lenin and joined the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party, a Marxist group.

Out of school, Stalin briefly worked as a part-time clerk in a meteorological office, but after a state crackdown on revolutionaries, he went underground and became a full-time revolutionary, living off donations.

When Lenin formed the Bolsheviks, Stalin eagerly joined up with him. Stalin proved to be a very effective organizer of men as well as a capable intellectual. Among other activities, he distributed propaganda, provoked strikes, staged bank robberies, and ordered assassinations. He was arrested and exiled to Siberia numerous times, but often escaped. His skill and charm won him the respect of Lenin, and he rose rapidly through the ranks of the Bolsheviks.

Stalin married his first wife, Ekaterina Svanidze, in 1906, who bore him a son. She died the following year of typhus. In 1911, he met his future second wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, during one of his many exiles in Siberia.

Revolution, Civil War, and Polish-Soviet War

Role during the Russian Revolution of 1917

After returning to Petrograd from his final exile, Stalin ousted Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov as editors of Pravda. He then took a position in favor of supporting Alexander Kerensky's provisional government. However, after Lenin prevailed at the April 1917 Communist Party conference, Stalin and Pravda shifted to opposing the provisional government. At this conference, Stalin was elected to the Bolshevik Central Committee. In October 1917, the Bolshevik Central Committee voted in favor of an insurrection. On 7 November, from the Smolny Institute, Trotsky, Lenin and the rest of the Central Committee coordinated the insurrection against Kerensky in the 1917 October Revolution. By 8 November, the Bolsheviks had stormed theWinter Palace and Kerensky's Cabinet had been arrested.

Role in the Russian Civil War, 1917–1919

Upon seizing Petrograd, Stalin was appointed People's Commissar for Nationalities' Affairs. Thereafter, civil war broke out in Russia, pitting Lenin's Red Army against the White Army, a loose alliance of anti-Bolshevik forces. Lenin formed a five-member Politburo, which included Stalin and Trotsky. In May 1918, Lenin dispatched Stalin to the city of Tsaritsyn. Through his new allies,Kliment Voroshilov and Semyon Budyonny, Stalin imposed his influence on the military.[citation needed]

Stalin challenged many of the decisions of Trotsky, ordered the killings of many counter-revolutionaries and former Tsarist officers in the Red Army[citation needed] and burned villages in order to intimidate the peasantry into submission and discourage bandit raids on food shipments.[citation needed] In May 1919, in order to stem mass desertions on the Western front, Stalin had deserters and renegades publicly executed as traitors.[15]

Role in the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–1921

After the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War, the Soviet Russia started the push towards a world revolution. It was part of the communist ideology to transform the whole world into socialist states. (Tukhachevsky: "There can be no doubt that if we had been victorious on the Vistula (i.e. in Poland), the revolutionary fires would have reached the entire continent."[16]). As a natural direction was the Western Europe, the bolsheviks had to conquer a newly reborn independent state of Poland. That was the beginning of what became known as the Polish–Soviet War. After initial succeses of Polish Army, the Bolsheviks pushed them back into central Poland. As the people's commisair to high command of the southern front, Stalin was determined to take the then Polish city of Lwów (now Lviv in Ukraine). This conflicted with the general strategy set by Lenin and Trotsky, which focused on the capture of Warsaw further north.

Tukhachevsky's forces engaged those of Polish commanders Józef Piłsudski and Władysław Sikorski at the pivotal Battle of Warsaw, but Stalin refused to redirect his troops from Lwów to help. Consequently, the four invading armies of Soviet Russia fighting for the Polish capital were totally routed by Poles, and the battles for both Lwów and Warsaw were lost, and Stalin was blamed. In August 1920, Stalin returned to Moscow, where he defended himself and resigned his military command. At the Ninth Party Conference on 22 September, Trotsky openly criticized Stalin's behavior.

Rise to power

Main article: Rise of Joseph Stalin

Stalin played a decisive role in engineering the 1921 Red Army invasion of Georgia, following which he adopted particularly hardline, centralist policies towards Soviet Georgia. This led to theGeorgian Affair of 1922 and other repressions.[17][18] Stalin's actions in Georgia created a rift with Lenin, who believed that all the Soviet states should stand equal.

Lenin nonetheless considered Stalin to be a loyal ally, and when he got mired in squabbles with Trotsky and other politicians, he decided to give Stalin more power. With the help of Lev Kamenev, Lenin had Stalin appointed General Secretary in 1922.[19] This post enabled Stalin to appoint many of his allies to government positions.

Lenin suffered a stroke in 1922, forcing him into semi-retirement in Gorki. Stalin visited him often, acting as his intermediary with the outside world,[19] but the pair quarreled and their relationship deteriorated.[19] Lenin dictated increasingly disparaging notes on Stalin in what would become his testament. He criticized Stalin's political views, rude manners, and excessive power and ambition, and suggested that Stalin should be removed from the position of general secretary.[19] During Lenin's semi-retirement, Stalin forged an alliance with Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev against Trotsky. These allies prevented Lenin's Testament from being revealed to the Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923[19] (after Lenin's death the testament was read to selected groups of deputies to the Thirteenth Party Congress in May 1924 but it was forbidden to be mentioned at the plenary assemblies or any documents of the Congress[20] ).

Lenin died of a heart attack on 21 January 1924. Following Lenin's death, a power struggle began, which involved following seven Politburo members:[21] Nikolai Bukharin, Lev Kamenev, Alexei Rykov, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Tomsky, Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev.

Again, Kamenev and Zinoviev helped to keep Lenin's Testament from going public. Thereafter, Stalin's disputes with Kamenev and Zinoviev intensified. Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev grew increasingly isolated, and were eventually ejected from the Central Committee and then from the Party itself.[19] Kamenev and Zinoviev were later readmitted, but Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union.

The Northern Expedition in China became a point of contention over foreign policy by Stalin and Trotsky. Stalin wanted the Communist Party of China to ally itself with the NationalistKuomintang, rather than attempt to implement a communist revolution. Trotsky urged the party to oppose the Kuomintang and launch a full-scale revolution. Stalin funded the KMT during the expedition.[22] Stalin countered Trotsky's criticisms by making a secret speech in which he said that the Kuomintang were the only ones capable of defeating the imperialists, that Chiang Kai-shek had funding from the rich merchants, and that his forces were to be utilized until squeezed for all usefulness like a lemon before being discarded.[23] However, Chiang quickly reversed the tables in the Shanghai massacre of 1927 by massacring the membership of the Communist party in Shanghai midway through the Northern Expedition.[24][25]

Stalin pushed for more rapid industrialization and central control of the economy, contravening Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP). At the end of 1927, a critical shortfall in grain supplies prompted Stalin to push for the collectivisation of agriculture and order the seizure of grain hoards from kulak farmers.[19][26] Nikolai Bukharin and Premier Alexey Rykov opposed these policies and advocated a return to the NEP, but the rest of the Politburo sided with Stalin and removed Bukharin from the Politburo in November 1929. Rykov was fired the following year and was replaced by Vyacheslav Molotov on Stalin's recommendation.

In December 1934, the popular Communist Party boss in Leningrad, Sergei Kirov, was murdered. Stalin blamed Kirov's murder on a vast conspiracy of saboteurs and Trotskyites. He launched a massive purge against these internal enemies, putting them on rigged show trials and then having them executed or imprisoned in Siberian Gulags. Among these victims were old enemies, including Bukharin, Rykov, Kamenev and Zinoviev. Stalin made the loyal Nikolai Yezhov head of the secret police, the NKVD, and had him purge the NKVD of veteran Bolsheviks. With no serious opponents left in power, Stalin ended the purges in 1938. Yezhov was held to blame for the excesses of the Great Terror. He was dismissed from office and later executed.

Changes to Soviet society, 1927–1939

Bolstering Soviet secret service and intelligence

Main article: Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies

| Part of the series on |

| Communism |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Stalinism |

|---|

|

Politics portal |

Stalin vastly increased the scope and power of the state's secret police and intelligence agencies. Under his guiding hand, Soviet intelligence forces began to set up intelligence networks in most of the major nations of the world, including Germany (the famous Rote Kappelle spy ring), Great Britain, France, Japan, and the United States. Stalin made considerable use of theCommunist International movement in order to infiltrate agents and to ensure that foreign Communist parties remained pro-Soviet and pro-Stalin.

One of the best examples of Stalin's ability to integrate secret police and foreign espionage came in 1940, when he gave approval to the secret police to have Leon Trotsky assassinated in Mexico.[27]

Cult of personality

Main article: Stalin's cult of personality

Stalin created a cult of personality in the Soviet Union around both himself and Lenin. Many personality cults in history have been frequently measured and compared to his. Numerous towns, villages and cities were renamed after the Soviet leader (see List of places named after Stalin) and the Stalin Prize and Stalin Peace Prize were named in his honor. He accepted grandiloquent titles (e.g., "Coryphaeus of Science," "Father of Nations," "Brilliant Genius of Humanity," "Great Architect of Communism," "Gardener of Human Happiness," and others), and helped rewrite Soviet history to provide himself a more significant role in the revolution of 1917. At the same time, according to Nikita Khrushchev, he insisted that he be remembered for "the extraordinary modesty characteristic of truly great people."[28] Statues of Stalin depict him at a height and build approximating the very tall Tsar Alexander III, while photographic evidence suggests he was between 5 ft 5 in and 5 ft 6 in (165–168 cm).[29]

Trotsky criticized the cult of personality built around Stalin. It reached new levels during World War II, with Stalin's name included in the new Soviet national anthem. Stalin became the focus of literature, poetry, music, paintings and film that exhibited fawning devotion. He was sometimes credited with almost god-like qualities, including the suggestion that he single-handedly won the Second World War. The degree to which Stalin himself relished the cult surrounding him is debatable. The Finnish communist Arvo Tuominen records a sarcastic toast proposed by Stalin at a New Year Party in 1935 in which he said "Comrades! I want to propose a toast to our Patriarch, life and sun, liberator of nations, architect of socialism [he rattled off all the appellations applied to him in those days] – Josef Vissarionovich Stalin, and I hope this is the first and last speech made to that genius this evening."[30]

In a 1956 speech, Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin's cult of personality with these words: "It is impermissible and foreign to the spirit of Marxism-Leninism to elevate one person, to transform him into a superman possessing supernatural characteristics akin to those of a god."[citation needed]

Purges and deportations

Purges and executions

Main article: Great Purge

Stalin, as head of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, consolidated near-absolute power in the 1930s with a Great Purge of the party that was justified as an attempt to expel "opportunists" and "counter-revolutionary infiltrators".[31][32] Those targeted by the purge were often expelled from the party, however more severe measures ranged from banishment to the Gulag labor camps to execution after trials held by NKVD troikas.[31][33][34]

In the 1930s, Stalin apparently became increasingly worried about the growing popularity of the Leningrad party boss Sergei Kirov. At the 1934 Party Congress where the vote for the new Central Committee was held, Kirov received only three negative votes, the fewest of any candidate, while Stalin received at least over a hundred negative votes.[35][36] After the assassination of Kirov, which may have been orchestrated by Stalin, Stalin invented a detailed scheme to implicate opposition leaders in the murder, including Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev.[37] The investigations and trials expanded.[38] Stalin passed a new law on "terrorist organizations and terrorist acts" that were to be investigated for no more than ten days, with no prosecution, defense attorneys or appeals, followed by a sentence to be executed "quickly."[39]

Thereafter, several trials known as the Moscow Trials were held, but the procedures were replicated throughout the country. Article 58 of the legal code, which listed prohibited anti-Soviet activities as counterrevolutionary crime, was applied in the broadest manner.[40] The flimsiest pretexts were often enough to brand someone an "enemy of the people", starting the cycle of public persecution and abuse, often proceeding to interrogation, torture and deportation, if not death. The Russian word troika gained a new meaning: a quick, simplified trial by a committee of three subordinated to NKVD -NKVD troika- with sentencing carried out within 24 hours.[39] Stalin's hand-picked executioner, Vasili Blokhin, was entrusted with carrying out some of the high profile executions in this period.[41]

Many military leaders were convicted of treason and a large-scale purge of Red Army officers followed.[43] The repression of so many formerly high-ranking revolutionaries and party members led Leon Trotsky to claim that a "river of blood" separated Stalin's regime from that of Lenin.[44] In August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico, where he had lived in exile since January 1937; this eliminated the last of Stalin's opponents among the former Party leadership.[45]

With the exception of Vladimir Milyutin (who died in prison in 1937) and Joseph Stalin himself, all of the members of Lenin's original cabinet who had not succumbed to death from natural causes before the purge were executed.

Mass operations of the NKVD also targeted "national contingents" (foreign ethnicities) such as Poles, ethnic Germans, Koreans, etc. A total of 350,000 (144,000 of them Poles) were arrested and 247,157 (110,000 Poles) were executed.[26] Many Americans who had emigrated to the Soviet Union during the worst of the Great Depression were executed; others were sent to prison camps orgulags.[46][47] Concurrent with the purges, efforts were made to rewrite the history in Soviet textbooks and other propaganda materials. Notable people executed by NKVD were removed from the texts and photographs as though they never existed. Gradually, the history of revolution was transformed to a story about just two key characters: Lenin and Stalin.

In light of revelations from Soviet archives, historians now estimate that nearly 700,000 people (353,074 in 1937 and 328,612 in 1938) were executed in the course of the terror,[48] with the great mass of victims merely "ordinary" Soviet citizens: workers, peasants, homemakers, teachers, priests, musicians, soldiers, pensioners, ballerinas, beggars.[49][50] Many of the executed were interred inmass graves, with some of the major killing and burial sites being Bykivnia, Kurapaty and Butovo.[51]

Some Western experts believe the evidence released from the Soviet archives is understated, incomplete or unreliable.[52][53][54][55][56]

Stalin personally signed 357 proscription lists in 1937 and 1938 that condemned to execution some 40,000 people, and about 90% of these are confirmed to have been shot.[57] At the time, while reviewing one such list, Stalin reportedly muttered to no one in particular: "Who's going to remember all this riff-raff in ten or twenty years time? No one. Who remembers the names now of the boyarsIvan the Terrible got rid of? No one."[58] In addition, Stalin dispatched a contingent of NKVD operatives to Mongolia, established a Mongolian version of the NKVD troika, and unleashed a bloody purgein which tens of thousands were executed as "Japanese Spies." Mongolian ruler Khorloogiin Choibalsan closely followed Stalin's lead.[59]

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Soviet leadership sent NKVD squads into other countries to murder defectors and other opponents of the Soviet regime. Victims of such plots included Yevhen Konovalets, Ignace Poretsky, Rudolf Klement, Alexander Kutepov, Evgeny Miller, Leon Trotsky and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) leadership in Catalonia (e.g., Andreu Nin).[60]

Deportations

Main article: Population transfer in the Soviet Union

Shortly before, during and immediately after World War II, Stalin conducted a series of deportations on a huge scale that profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union. It is estimated that between 1941 and 1949 nearly 3.3 million[61][62] were deported to Siberia and the Central Asian republics. By some estimates up to 43% of the resettled population died of diseases andmalnutrition.[63]

Separatism, resistance to Soviet rule and collaboration with the invading Germans were cited as the official reasons for the deportations, rightly or wrongly. Individual circumstances of those spending time in German-occupied territories were not examined. After the brief Nazi occupation of the Caucasus, the entire population of five of the small highland peoples and the Crimean Tatars – more than a million people in total – were deported without notice or any opportunity to take their possessions.[64]

As a result of Stalin's lack of trust in the loyalty of particular ethnicities, ethnic groups such as the Soviet Koreans, the Volga Germans, the Crimean Tatars, the Chechens, and many Poles were forcibly moved out of strategic areas and relocated to places in the central Soviet Union, especially Kazakhstan in Soviet Central Asia. By some estimates, hundreds of thousands of deportees may have died en route.[61]

According to official Soviet estimates, more than 14 million people passed through the Gulag from 1929 to 1953, with a further 7 to 8 million being deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union (including the entire nationalities in several cases).[65]

In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev condemned the deportations as a violation of Leninism, and reversed most of them, although it was not until 1991 that the Tatars, Meskhetians and Volga Germans were allowed to return en masse to their homelands. The deportations had a profound effect on the peoples of the Soviet Union. The memory of the deportations has played a major part in the separatist movements in the Baltic States, Tatarstan and Chechnya, even today.

Collectivization

Main article: Collectivization in the Soviet Union

Stalin's regime moved to force collectivization of agriculture. This was intended to increase agricultural output from large-scale mechanized farms, to bring the peasantry under more direct political control, and to make tax collection more efficient. Collectivization brought social change on a scale not seen since the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and alienation from control of the land and its produce. Collectivization also meant a drastic drop in living standards for many peasants, and it faced violent reaction among the peasantry.

In the first years of collectivization it was estimated that industrial production would rise by 200% and agricultural production by 50%,[66] but these expectations were not realized. Stalin blamed this unanticipated failure on kulaks (rich peasants), who resisted collectivization. However, kulaks proper made up only 4% of the peasant population; the "kulaks" that Stalin targeted included the slightly better-off peasants who took the brunt of violence from the OGPU and the Komsomol. These peasants were about 60% of the population. Those officially defined as "kulaks", "kulak helpers", and, later, "ex-kulaks" were to be shot, placed into Gulag labor camps, or deported to remote areas of the country, depending on the charge. Archival data indicates that 20,201 people were executed during 1930, the year of Dekulakization.[59]

The two-stage progress of collectivization—interrupted for a year by Stalin's famous editorials, "Dizzy with Success"[67] and "Reply to Collective Farm Comrades"[68]—is a prime example of his capacity for tactical political withdrawal followed by intensification of initial strategies.

Famines

Main article: Soviet famine of 1932–1933

Famine affected other parts of the USSR. The death toll from famine in the Soviet Union at this time is estimated at between 5 and 10 million people.[69] The worst crop failure of late tsarist Russia, in 1892, had caused 375,000 to 400,000 deaths.[70] Most modern scholars agree that the famine was caused by the policies of the government of the Soviet Union under Stalin, rather than by natural reasons.[71] According to Alan Bullock, "the total Soviet grain crop was no worse than that of 1931 ... it was not a crop failure but the excessive demands of the state, ruthlessly enforced, that cost the lives of as many as five million Ukrainian peasants." Stalin refused to release large grain reserves that could have alleviated the famine, while continuing to export grain; he was convinced that the Ukrainian peasants had hidden grain away and strictly enforced draconian new collective-farm theft laws in response.[72][73] Other historians hold it was largely the insufficient harvests of 1931 and 1932 caused by a variety of natural disasters that resulted in famine, with the successful harvest of 1933 ending the famine.[74] Soviet and other historians have argued that the rapid collectivization of agriculture was necessary in order to achieve an equally rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union and ultimately win World War II. Alec Nove claims that the Soviet Union industrialized in spite of, rather than because of, its collectivized agriculture.[citation needed]

The USSR also experienced a major famine in 1947 as a result of war damage and severe droughts, but economist Michael Ellman argues that it could have been prevented if the government had not mismanaged its grain reserves. The famine cost an estimated 1 to 1.5 million lives as well as secondary population losses due to reduced fertility.[75]

Ukrainian famine

Main article: Holodomor

The Holodomor famine is sometimes referred to as the Ukrainian Genocide, implying it was engineered by the Soviet government, specifically targeting the Ukrainian people to destroy the Ukrainian nation as a political factor and social entity.[76][77][78][79] While historians continue to disagree whether the policies that led to Holodomor fall under the legal definition of genocide, twenty-six countries have officially recognized the Holodomor as such. On 28 November 2006, the Ukrainian Parliament approved a bill declaring the Soviet-era forced famine an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.[80] Professor Michael Ellman concludes that Ukrainians were victims of genocide in 1932–33 according to a more relaxed definition that is favored by some specialists in the field of genocide studies. He asserts that Soviet policies greatly exacerbated the famine's death toll. Although 1.8 million tonnes of grain were exported during the height of the starvation—enough to feed 5 million people for one year-the use of torture and execution to extract grain under the Law of Spikelets, the use of force to prevent starving peasants from fleeing the worst-affected areas, and the refusal to import grain or secure international humanitarian aid to alleviate conditions led to incalculable human suffering in the Ukraine. It would appear that Stalin intended to use the starvation as a cheap and efficient means (as opposed to deportations and shootings) to kill off those deemed to be "counterrevolutionaries," "idlers," and "thieves," but not to annihilate the Ukrainian peasantry as a whole. Ellman also claims that, while this was not the only Soviet genocide (e.g., the Polish operation of the NKVD), it was the worst in terms of mass casualties.[57]

Current estimates on the total number of casualties within Soviet Ukraine range mostly from 2.2 million[81][82] to 4 to 5 million.[83][84][85]

A Ukrainian court found Josef Stalin and other leaders of the former Soviet Union guilty of genocide by "organizing mass famine in Ukraine in 1932–1933" in January 2010. However, the court "dropped criminal proceedings over the suspects' deaths".[86][87]

Industrialization

The Russian Civil War and wartime communism had a devastating effect on the country's economy. Industrial output in 1922 was 13% of that in 1914. A recovery followed under the New Economic Policy, which allowed a degree of market flexibility within the context of socialism. Under Stalin's direction, this was replaced by a system of centrally ordained "Five-Year Plans" in the late 1920s. These called for a highly ambitious program of state-guided crash industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture.

With seed capital unavailable because of international reaction to Communist policies, little international trade, and virtually no modern infrastructure, Stalin's government financed industrialization both by restraining consumption on the part of ordinary Soviet citizens to ensure that capital went for re-investment into industry and by ruthless extraction of wealth from the kulaks.

In 1933 workers' real earnings sank to about one-tenth of the 1926 level.[citation needed] Common and political prisoners in labor camps were forced to perform unpaid labor, and communists andKomsomol members were frequently "mobilized" for various construction projects. The Soviet Union used numerous foreign experts to design new factories, supervise construction, instruct workers, and improve manufacturing processes. The most notable foreign contractor was Albert Kahn's firm that designed and built 521 factories between 1930 and 1932. As a rule, factories were supplied with imported equipment.

In spite of early breakdowns and failures, the first two Five-Year Plans achieved rapid industrialization from a very low economic base. While it is generally agreed that the Soviet Union achieved significant levels of economic growth under Stalin, the precise rate of growth is disputed. It is not disputed, however, that these gains were accomplished at the cost of millions of lives. Official Soviet estimates stated the annual rate of growth at 13.9%; Russian and Western estimates gave lower figures of 5.8% and even 2.9%. Indeed, one estimate is that Soviet growth became temporarily much higher after Stalin's death.[88][89]

According to Robert Lewis, the Five-Year Plan substantially helped to modernize the previously backward Soviet economy. New products were developed, and the scale and efficiency of existing production greatly increased. Some innovations were based on indigenous technical developments, others on imported foreign technology.[90] Despite its costs, the industrialization effort allowed the Soviet Union to fight, and ultimately win, World War II.

Science

Main articles: Science and technology in the Soviet Union and Suppressed research in the Soviet Union

Science in the Soviet Union was under strict ideological control by Stalin and his government, along with art and literature. There was significant progress in "ideologically safe" domains, owing to the free Soviet education system and state-financed research. However, the most notable legacy during Stalin's time was his public endorsement of the agronomist Trofim Lysenko, who rejected Mendelian genetics as "bourgeois pseudoscience" and instead advocated Lamarckian inheritance and hybridization theories (which had been discredited by most Western countries by the 1920s in favor of Darwinian Evolution), that caused widespread agricultural destruction and major setbacks in Soviet knowledge in biology. Many scientists came out publicly against his views, but the majority of them, including Nikolai Vavilov (who was later hailed as a pioneer in modern Genetics), were imprisoned or executed. Some areas of physics were criticized.[91][92]

Social services

Under the Soviet government people benefited from some social liberalization. Girls were given an adequate, equal education and women had equal rights in employment,[26] improving lives for women and families. Stalinist development also contributed to advances in health care, which significantly increased the lifespan and quality of life of the typical Soviet citizen.[26] Stalin's policies granted the Soviet people universal access to healthcare and education, effectively creating the first generation free from the fear of typhus, cholera, and malaria.[26] The occurrences of these diseases dropped to record low numbers, increasing life spans by decades.[26]

Soviet women under Stalin were the first generation of women able to give birth in the safety of a hospital with access to prenatal care.[26] Education was also an example of an increase in the standard of living after economic development. The generation born during Stalin's rule was the first near-universally literate generation. Millions benefited from mass literacy campaigns in the 1930s, and from workers training schemes.[93] Engineers were sent abroad to learn industrial technology, and hundreds of foreign engineers were brought to Russia on contract.[26] Transport links were improved and many new railways built. Workers who exceeded their quotas, Stakhanovites, received many incentives for their work;[93] they could afford to buy the goods that were mass-produced by the rapidly expanding Soviet economy.

The increase in demand due to industrialization and the decrease in the workforce due to World War II and repressions generated a major expansion in job opportunities for the survivors, especially for women.[93]

Culture

Main article: Socialist Realism

Although he was Georgian by birth, some western historians claim that Stalin became a Russian nationalist[94] and significantly promoted Russian history, language, and Russian national heroes, particularly during the 1930s and 1940s.[citation needed] There are also claims that he held the Russian people up as the elder brothers of the non-Russian minorities.[95]

During Stalin's reign the official and long-lived style of Socialist Realism was established for painting, sculpture, music, drama and literature. Previously fashionable "revolutionary"expressionism, abstract art, and avant-garde experimentation were discouraged or denounced as "formalism".

The degree of Stalin's personal involvement in general, and in specific instances, has been the subject of discussion.[citation needed] Stalin's favorite novel Pharaoh, shared similarities[citation needed] with Sergei Eisenstein's film, Ivan the Terrible, produced under Stalin's tutelage.

In architecture, a Stalinist Empire Style (basically, updated neoclassicism on a very large scale, exemplified by the Seven Sisters of Moscow) replaced the constructivism of the 1920s. Stalin's rule had a largely disruptive effect on indigenous cultures within the Soviet Union, though the politics of Korenizatsiya and forced development were possibly beneficial to the integration of later generations of indigenous cultures.

Religion

Main article: Religion in the Soviet Union

Raised in the Georgian Orthodox faith, Stalin became an atheist. He followed the position that religion was an opiate that needed to be removed in order to construct the ideal communist society. His government promoted atheism through special atheistic education in schools, anti-religious propaganda, the antireligious work of public institutions (Society of the Godless), discriminatory laws, and a terror campaign against religious believers. By the late 1930s it had become dangerous to be publicly associated with religion.[96]

Stalin's role in the fortunes of the Russian Orthodox Church is complex. Continuous persecution in the 1930s resulted in its near-extinction as a public institution: by 1939, active parishes numbered in the low hundreds (down from 54,000 in 1917), many churches had been leveled, and tens of thousands of priests, monks and nuns were persecuted and killed. Over 100,000 were shot during the purges of 1937–1938.[97][98] During World War II, the Church was allowed a revival as a patriotic organization, and thousands of parishes were reactivated until a further round of suppression during Khrushchev's rule. The Russian Orthodox Church Synod's recognition of the Soviet government and of Stalin personally led to a schism with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia.

Just days before Stalin's death, certain religious sects were outlawed and persecuted. Many religions popular in ethnic regions of the Soviet Union, including the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Catholic Churches, Baptists, Islam,Buddhism, and Judaism underwent ordeals similar to that which the Orthodox churches in other parts of the country suffered: thousands of monks were persecuted, and hundreds of churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, sacred monuments, monasteries and other religious buildings were razed. Stalin had a different policy outside the Soviet Union; he supported the Communist Uyghur Muslim separatists under Ehmetjan Qasim in the Ili Rebellion against the Anti Communist Republic of China regime. He supplied weapons to the Uyghur Ili army and Red Army support against Chinese forces, and helped them establish the Second East Turkestan Republic of which Islam was the official state religion.

Theorist

Main article: Stalinism

Stalin and his supporters have highlighted the notion that socialism can be built and consolidated by a country ("Socialism in One Country") as underdeveloped as Russia during the 1920s. Indeed this might be the only means in which it could be built in a hostile environment.[99] In 1933, Stalin put forward the theory of aggravation of the class struggle along with the development of socialism, arguing that the further the country would move forward, the more acute forms of struggle will be used by the doomed remnants of exploiter classes in their last desperate efforts – and that, therefore, political repression was necessary.

In 1936, Stalin announced that the society of the Soviet Union consisted of two non-antagonistic classes: workers and kolkhoz peasantry. These corresponded to the two different forms of property over the means of production that existed in the Soviet Union: state property (for the workers) and collective property (for the peasantry). In addition to these, Stalin distinguished the stratum of intelligentsia. The concept of "non-antagonistic classes" was entirely new to Leninist theory. Among Stalin's contributions to Communist theoretical literature were "Dialectical and Historical Materialism," "Marxism and the National Question", "Trotskyism or Leninism", and "The Principles of Leninism."

Calculating the number of victims

Before the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, researchers who attempted to count the number of people killed under Stalin's regime produced estimates ranging from 3 to 60 million.[100] After the Soviet Union dissolved, evidence from the Soviet archives also became available, containing official records of 799,455 executions 1921–53,[101] around 1.7 million deaths in the Gulag and some 390,000 deaths during kulak forced resettlement – with a total of about 2.9 million officially recorded victims in these categories.[102]

The official Soviet archival records do not contain comprehensive figures for some categories of victims, such as those of ethnic deportations or of German population transfers in the aftermath of World War II.[103] Eric D. Weitz wrote, "By 1948, according to Nicolas Werth, the mortality rate of the 600,000 people deported from the Caucasus between 1943 and 1944 had reached 25%."[104][105] Other notable exclusions from NKVD data on repression deaths include the Katyn massacre, other killings in the newly occupied areas, and the mass shootings of Red Armypersonnel (deserters and so-called deserters) in 1941. The Soviets executed 158,000 soldiers for desertion during the war,[106] and the "blocking detachments" of the NKVD shot thousands more.[107] Also, the official statistics on Gulag mortality exclude deaths of prisoners taking place shortly after their release but which resulted from the harsh treatment in the camps.[108] Some historians also believe that the official archival figures of the categories that were recorded by Soviet authorities are unreliable and incomplete.[109][110] In addition to failures regarding comprehensive recordings, as one additional example, Robert Gellately and Simon Sebag Montefiore argue that the many suspects beaten and tortured to death while in "investigative custody" were likely not to have been counted amongst the executed.[26][111]

Historians working after the Soviet Union's dissolution have estimated victim totals ranging from approximately 4 million to nearly 10 million, not including those who died in famines.[112][113][114]Russian writer Vadim Erlikman, for example, makes the following estimates: executions, 1.5 million; gulags, 5 million; deportations, 1.7 million out of 7.5 million deported; and POWs and German civilians, 1 million – a total of about 9 million victims of repression.[115]

Some have also included the deaths of 6 to 8 million people in the 1932–1933 famine among the victims of Stalin's repression. This categorization is controversial however, as historians differ as to whether the famine was a deliberate part of the campaign of repression against kulaks and others,[57][116][117][118][119] or simply an unintended consequence of the struggle over forced collectivization.[73][120][121]

Accordingly, if famine victims are included, a minimum of around 10 million deaths—6 million from famine and 4 million from other causes—are attributable to the regime,[122] with a number of recent historians suggesting a likely total of around 20 million, citing much higher victim totals from executions, Gulag camps, deportations and other causes.[123][124][125][126][127][128][129] Adding 6–8 million famine victims to Erlikman's estimates above, for example, would yield a total of between 15 and 17 million victims. Researcher Robert Conquest, meanwhile, has revised his original estimate of up to 30 million victims down to 20 million.[130] In his most recent edition of The Great Terror (2007), Conquest states that while exact numbers may never be known with complete certainty, the various terror campaigns launched by the Soviet government claimed no fewer than 15 million lives.[131] RJ Rummel maintains that the earlier higher victim total estimates are correct, although he includes those killed by the Soviet government in other Eastern European countries as well.[132][133]

No comments:

Post a Comment