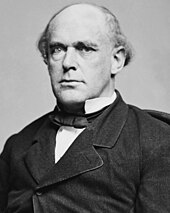

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) served as the 20th President of the United States (1881), after completing nine consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1863–81).

Garfield's accomplishments as President included a controversial resurgence of Presidential authority above Senatorial courtesy in executive appointments; energizing U.S. naval power; and purging corruption in the Post Office Department. Garfield made notable diplomatic and judiciary appointments, including a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Garfield appointed several African-Americans to prominent federal positions. As President, Garfield advocated a bi-metal monetary system, agricultural technology, an educated electorate, and civil rights for African-Americans. He proposed substantial civil service reform, eventually passed by Congress in 1883 and signed into law by his successor, Chester A. Arthur, as the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act.

Garfield's presidency lasted just 200 days—from March 4, 1881, until his death on September 19, 1881, as a result of being shot by assassin Charles J. Guiteau on July 2, 1881. Only William Henry Harrison's presidency, of 31 days, was shorter. Garfield was the second of four United States Presidents who were assassinated.

Garfield was raised in humble circumstances on an Ohio farm by his widowed mother and elder brother, next door to their cousins, the Boyntons, with whom he remained very close. He worked at many jobs to finance his higher education at Williams College, Massachusetts, from which he graduated in 1856.

A year later, Garfield entered politics as a Republican, after campaigning for the party's anti-slavery platform in Ohio. He married Lucretia Rudolph in 1858 and, in 1860, was admitted to practice law while serving as an Ohio State Senator (1859–1861). Garfield opposed Confederate secession, served as a major general in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and fought in the battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh and Chickamauga. He was first elected to Congress in 1862 as Representative of the 19th District of Ohio.

Throughout Garfield's extended Congressional service after the Civil War, he fervently opposed the Greenback, and gained a reputation as a skilled orator. He was Chairman of the Military Affairs Committee and the Appropriations Committee and a member of the Ways and Means Committee. Garfield initially agreed with Radical Republican views regarding Reconstruction, then favored a moderate approach for civil rights enforcement for Freedmen.

In 1880, the Ohio legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate; in that same year, the leading Republican presidential contenders – Ulysses S. Grant, James G. Blaine and John Sherman – failed to garner the requisite support at their convention. Garfield became the party's compromise nominee for the 1880 Presidential Election and successfully campaigned to defeat DemocratWinfield Hancock in the election. He is thus far the only sitting Representative to have been elected to the presidency.

Contents

[show]Childhood[edit]

James Garfield was born the youngest of five children on November 19, 1831, in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio. His uncle Amos and aunt Alpha Boynton lived next door. The families were very close as Amos was James' father's half brother, and Alpha was his mother's sister. James and his Boynton cousins cherished their memories of childhood together.

His father, Abram Garfield, known locally as a wrestler, died when Garfield was 18 months old.[3][4] He was reared and cared for by his mother, Eliza (née Ballou), who said, "He was the largest babe I had and looked like a red Irishman."[5] Garfield's parents joined the Church of Christ (also known at the time as Disciples of Christ), which profoundly influenced their son.[6] Garfield was able to receive rudimentary education at a village school in Orange, listening and discussing books read. Garfield knew he needed money to advance his learning.[7]

At age 16, he moved out on his own with dreams of being a seaman, and got a job for six weeks as a canal driver near Cleveland.[8] Illness forced him to return home and, once recuperated, he began school at Geauga Seminary, where he became keenly interested in academics, both learning and teaching.[9] Garfield worked as a janitor, bell ringer, and carpenter to support himself financially at the Geauga Seminary, at Chester, Ohio.[10][11] Garfield later said of this early time, "I lament that I was born to poverty, and in this chaos of childhood, seventeen years passed before I caught any inspiration...a precious 17 years when a boy with a father and some wealth might have become fixed in manly ways."[12] In 1849, he accepted an unsought position as a teacher, and thereafter developed an aversion to what he called "place seeking," which became, he said, "the law of my life."[13] In 1850 Garfield resumed his church attendance and was baptized.[14]

Education, marriage and early career[edit]

From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio. While at Eclectic, he was most interested in the study of Greek and Latin,[15] and he was also engaged to teach. He developed a regular preaching circuit at neighboring churches, in some cases earning a gold dollar per service.[16] Garfield then enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he joined the Delta Upsilonfraternity[17] and graduated in 1856 as an outstanding student.[18] Garfield was quite impressed with the college President, Mark Hopkins, about whom he said, "The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log with a student on the other." Garfield earned a reputation as a skilled debater and was made President of the Philogian Society and Editor of the Williams Quarterly.[19]

Garfield is the only President of the United States to have been a clergyman. As a Minister for the Disciples of Christ, Garfield preached briefly at Franklin Circle Christian Church (1857–58). Garfield stopped preaching full time, though he would continue to preach on occasion until he resigned from the clergy when elected President, saying that "I resign the highest office in the land to become President of the United States."[20] In 1858, Garfield applied for a job as principal of a high school in Poestenkill, New York.[21] After another applicant had been chosen, he returned to teach at the Eclectic Institute. Garfield was an instructor in classical languages for the 1856–1857 academic year and was made Principal of the Institute from 1857 to 1860, successfully restoring it to viability after it had fallen on hard times.[22] During this time, Garfield revealed himself to be sympathetic with the views of moderate Republicans, though he was not yet a party man. While he did not consider himself an abolitionist, he was opposed to slavery.[23] After Garfield finished his education, between the 1857 and 1858 elections, he began his career in politics as a "vigorous" stump speaker in support of the Republican Party and their anti-slavery cause. In 1858, a migrant freethinker and evolutionary named Denton challenged him to a debate (Charles Darwin's Origin of Species was published the next year). The debate, which lasted over a week, was considered as won convincingly by Garfield.[24]

Garfield's first romantic interest was Mary Hubbell in 1851, but it lasted only a year, with no formal engagement.[25] On November 11, 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph, known as "Crete" to friends, and a former star Greek pupil of Garfield's.[16] They had seven children (five sons and two daughters): Eliza Arabella Garfield (1860–63); Harry Augustus Garfield (1863–1942); James Rudolph Garfield (1865–1950); Mary Garfield (1867–1947); Irvin M. Garfield (1870–1951); Abram Garfield (1872–1958); and Edward Garfield (1874–76). One son, James R. Garfield, followed him into politics and became Secretary of the Interior under President Theodore Roosevelt.

Garfield gradually became discontented with teaching and began to study law in 1859.[26] He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1861.[27] Before admission to the bar, he was invited to enter politics by local Republican Party leaders upon the death of Cyrus Prentiss, the presumed nominee for the state senate seat for the 26th District in Ohio. He was nominated by the party convention and then elected an Ohio state senator in 1859, serving until 1861.[4] Garfield's signature effort in the state legislature was a bill providing for the state's first geological survey to measure its mineral resources.[28] His initial observations about the nation leading up to the Civil War were that secession was quite inconceivable.[29] His response was in part a renewed zeal for the July 4 celebrations in 1860.[30]

After Abraham Lincoln's election, Garfield was more inclined to arms than negotiations, saying, "Other states may arm to the teeth, but if Ohio so much as cleans her rusty muskets, it is said to have offended our brethren in the South. I am weary of this weakness."[31] On February 13, 1861, the newly elected President Lincoln arrived in Cincinnati by train to make a speech. Garfield observed that Lincoln was "distressingly homely", yet had "the tone and bearing of a fearless, firm man."[32]

Military career[edit]

Under Buell's command[edit]

At the start of the American Civil War, Garfield quickly grew frustrated with his vain efforts to obtain an officer's commission in the Union Army.[33] Ohio Governor William Dennison, Jr. charged him with a mission to travel to Illinois to acquire musketry and to negotiate with the Governors of Illinois and Indiana for the consolidation of troops.[34] In the summer of 1861 he was finally commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the Union Army and given command of the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry.[33]

General Don Carlos Buell assigned Colonel Garfield the task of driving Confederate forces out of eastern Kentucky in November 1861, giving him the 18th Brigade for the campaign. In December, he departed Catlettsburg, Kentucky, with the 40th Ohio Infantry, the 42nd Ohio Infantry, the 14th Kentucky Infantry, and the 22nd Kentucky Infantry, as well as the 2nd (West) Virginia Cavalry and McLoughlin's Squadron of Cavalry. The march was uneventful until Union forces reached Paintsville, Kentucky, on January 6, 1862, where Garfield's cavalry engaged the Confederates at Jenny's Creek. Garfield artfully positioned his troops so as to deceive Marshall into thinking that he was outnumbered, when in fact he was not.[35] The Confederates, under Brigadier GeneralHumphrey Marshall, withdrew to the forks of Middle Creek, two miles (3 km) from Prestonsburg, Kentucky, on the road to Virginia. Garfield attacked on January 9, 1862. At the end of the day's fighting the Confederates withdrew from the field, but Garfield did not pursue them, opting instead to withdraw to Prestonsburg so he could resupply his men. His victory brought him early recognition and he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general on January 11.[36]

Garfield later commanded the 20th Brigade of Ohio under Buell at the Battle of Shiloh, where he led troops in an attempt, delayed by weather, to reinforce Maj Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, after a surprise attack by Confederate General Albert S. Johnston.[37] He then served under Thomas J. Wood in the Siege of Corinth, where he assisted in the pursuit of Confederates in retreat by the overly cautious Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, which resulted in the escape of Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard and his troops. This engendered in the furious Garfield a lasting distrust of the training atWest Point.[38] Garfield's philosophy of war in 1862—to aggressively carry the war to Southern civilians—was not then shared by the Union leadership. The tactic was later adopted and demonstrated in the campaigns of Generals Sherman and Sheridan.[39]

Garfield made the following comment in 1862 concerning slavery: "...if a man is black, be he friend or foe, he is thought best kept at a distance. It is hardly possible God will let us succeed while such enormities are practiced."[40] That summer his health suddenly deteriorated, including jaundice and significant weight loss. (Biographer Peskin speculated this may have been infectious hepatitis.[41]) Garfield was forced to return home, where his wife nursed him back to health and their marriage was reinvigorated.[42] He returned to duty that autumn and served on the Court-martial of Fitz John Porter. Garfield was then sent to Washington to receive further orders. With great frustration, he repeatedly received tentative assignments, extended and later reversed, to stations in Florida, Virginia and South Carolina.[43] During this period of idleness in Washington waiting for an assignment, Garfield spent much of his time corresponding with old friends and family. An unsubstantiated rumor of an affair caused a brief friction in the Garfield marriage of which Lucretia graciously overlooked.[44]

Chief of staff for Rosecrans[edit]

In the spring of 1863, Garfield returned to the field as Chief of Staff for William Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland; his influence in this position was greater than usual – with duties extending beyond mere communication to actual management of Rosecrans's army.[45] Rosecrans, a highly energetic man, had a voracious appetite for conversation, which he deployed when he was unable to sleep; in Garfield he had found "the first well read person in the Army" and thus the ideal candidate for endless discussions through the night.[46] The two became close, and covered all topics, especially religion; Rosecrans, who with his brother had converted from Methodism to Catholicism, succeeded in softening Garfield's view of Catholicism.[47] Garfield, with his enhanced influence, created an intelligence corps unsurpassed in the Union Army.[48] He also recommended that Rosecrans should replace wing commanders Alexander McCook and Thomas Crittenden due to their prior ineffectiveness. Rosecrans ignored these recommendations, with drastic consequences later, in the Battle of Chickamauga.[49] Garfield crafted a campaign designed to pursue and then trap Confederate General Braxton Bragg in Tullahoma. The army advanced to that point with success, but Bragg retreated toward Chattanooga. Rosecrans then stalled his army's move against Bragg and made repeated requests for additional troops and supplies. Garfield argued with his superior for an immediate advance, also insisted upon by Lincoln and Rosecrans's commander, Gen. Halleck.[50] Garfield conceived a plan to conduct a cavalry raid behind Bragg's line (similar to that Bragg was employing against Rosecrans) which Rosecrans approved; the raid, led by Abel Streight, failed, due in part to poor execution and weather.[51] Garfield's detractors later claimed his concept was flawed.[52] To address the continued dispute over whether to advance, Rosecrans called a war council of his generals; 10 of the 15 were opposed to the move, with Garfield voting in favor. Nevertheless Garfield, in an unusual move, drew up a report of the council's deliberations, and thus convinced Rosecrans to proceed with an advance against Bragg.[53]

At the Battle of Chickamauga, Rosecrans issued an order which sought to fill a gap in his line, but which actually created one. As a result, his right flank was routed. Rosecrans concluded that the battle was lost and headed for Chattanooga to establish a defensive line. Garfield, however, thought that part of the army had held and, with Rosecrans's approval, headed across Missionary Ridge to survey the Union status. Garfield's hunch was correct; his ride became legendary, while Rosecrans' error reinforced critical opinions about his leadership.[54] While Rosecrans's army had avoided complete loss, they were left in Chattanooga surrounded by Bragg's army. Garfield sent a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton alerting Washington to the need for reinforcements to avoid annihilation. As a result, Lincoln and Halleck succeeded in delivering 20,000 troops to Chattanooga by rail within nine days.[55] One of Grant's early decisions upon assuming command of the Union Army was to replace Rosecrans with George H. Thomas.[56] Garfield was issued orders to report to Washington, where he was promoted to major general;[57] shortly thereafter he gave an unambiguously abolitionist speech in Maryland.[58] He was unsure of whether he should return to the field or assume the Ohio congressional seat he had won in October 1862. After a discussion with Lincoln, he decided in favor of the latter and resigned his commission.[59] According to historian Jean Edward Smith, Grant and Garfield had a "guarded relationship", since Grant put Thomas in charge of the Army of the Cumberland, rather than Garfield, after Rosecrans was dismissed.[60]

Garfield communicated his frustration with Rosecrans in a confidential letter to his friend, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Garfield's detractors later used this letter, which Chase never personally disclosed, to foster widespread criticism of Garfield as a betrayer, despite the fact that Halleck and Lincoln shared the same concerns over Rosecrans's reluctance to attack, and that Garfield had openly conveyed his concerns to Rosecrans.[61] In later years, Charles Dana of the New York Sun allegedly had sources indicating that Garfield had publicly stated that Rosecrans had fled the battlefield during the Battle of Chickamauga. According to biographer Peskin, the credibility of the information and the sources used are questionable.[62] According to historian Bruce Catton, Garfield's statements influenced the Lincoln administration to find a replacement for Rosecrans.[63]

Congressional career[edit]

Election in 1862 and first term[edit]

While serving in the army in early 1862, Garfield was approached by friends about political opportunities resulting from the redrawn 19th Ohio Congressional District; it was believed that the incumbent,John Hutchins, was vulnerable.[64] Garfield was conflicted; he was sure that he could better serve in Congress than in camp, but he was determined that his military position not be used as a stepping stone to political advancement. He therefore resorted to his long-held objection to "place-seeking", expressed a willingness to serve if elected, and otherwise left the matter to others.[65] Garfield was nominated at the Republican convention on the 75th roll call vote.[66] In October 1862 he defeated D.B. Woods by a two-to-one margin in the general election for the District's House seat in the 38th Congress.[67]

After the election, Garfield was anxious to determine his next military assignment and went to Washington for this purpose. While there, he developed a close alliance with Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary.[68] Garfield became a member of the Radical Republicans, led by Chase, in contrast with the moderate wing of the party, led by Lincoln and Montgomery Blair.[69] Garfield was as frustrated with Lincoln's lack of aggressiveness in pursuing the rebel enemy as Lincoln had been with Gen. McClellan.[70] Chase and Garfield shared a disdain for West Point and the President, though Garfield praised the Emancipation Proclamation.[71] Garfield also shared a negative view of General McClellan, whom he considered the epitome of the Democratic, pro-slavery, poorly trained West Point generals.[72]

Garfield became enthralled by the economic and financial policy discussions in Chase's office, and these subjects became his lifelong passion and expertise.[73] Like Chase, Garfield became a staunch proponent of "honest money" or "specie payment" backed by a gold standard, and was therefore a strong opponent of the "greenback"; he regretted very much, but understood, the necessity forsuspension of specie payment during the emergency presented by the Civil War.[74]

Although his desire was to continue his Army service, Garfield reluctantly took his seat in Congress upon resigning his military commission in December 1863. His first-born three-year-old child Eliza suddenly died that same month.[75] Although he initially took a room by himself, his grief over the death of Eliza compelled him to find a roommate, which he did—Robert C. Schenck.[76] After Garfield's term ended, Lucretia moved to Washington to be with her husband, and the two, thereafter, never lived apart.[77]

Garfield immediately showed an ability to command the attention of the unruly House. According to a reporter, "...when he takes the floor, Garfield's voice is heard above all others. Every ear attends...his eloquent words move the heart, convince the reason, and tell the weak and wavering which way to go."[78] He was one of the more hawkish Republicans in the House, and served on Schenck's Military Affairs Committee, which brought him prominence in the midst of the predominant war issues.[79] Garfield aggressively promoted the need for a military draft, an issue almost all others shunned.[80]

Early in his tenure, he differed from his party on several issues; his was the solitary Republican vote to terminate the use of bounties in recruiting. Some financially able recruits had used the bounty system to buy their way out of service (called commutation), which he considered reprehensible.[78] After many false starts, Garfield, with the support of Lincoln, procured the passage of an aggressive conscription bill which excluded commutation.[81] In 1864 Congress passed a bill to revive the rank of Lieutenant General. Garfield, who shared the opinion of Thaddeus Stevens, was not in favor of this action, because the rank was intended for Grant, who had dismissed Rosecrans. Also, the recipient would thereby be given an advantage in possibly opposing Lincoln in the next election. Garfield was nevertheless very tentative in his support for the President's re-election.[82]

Garfield, aligned with the Radical Republicans on some issues, not only favored abolition, but early in his career believed that the leaders of the rebellion had forfeited their constitutional rights. He supported the confiscation of southern plantations and even exile or execution of rebellion leaders as a means to ensure the permanent destruction of slavery.[83] He felt Congress was obliged "to determine what legislation is necessary to secure equal justice to all loyal persons, without regard to color."[84] With respect to the Presidential election of 1864, Garfield did not consider Lincoln particularly worthy of re-election, but no other viable alternative was available. "I have no candidate for President. I am a sad and sorrowful spectator of events."[85] He attended the party convention and promoted Rosecrans for the V.P. nomination; this was greeted by Rosecrans's characteristic indecision, so the nomination went to Andrew Johnson.[86]Garfield voted with the Radical Republicans in passing the Wade–Davis Bill, designed to give Congress more authority over Reconstruction, but the bill was defeated by Lincoln's pocket veto.[87]

1864 election and second term[edit]

In the 1864 Congressional election, Garfield's district base weakened due to his refusal to support Lincoln's re-election, but was reinvigorated when he reminded his constituents of his traditional disdain of partisanship; he was then nominated by acclamation and his re-election was assured.[88] While resting after the election, Lucretia gave him a note indicating they had been together only 20 out of the 57 weeks since his first election; he immediately resolved to take her and the family with him to live in Washington.[89] As the war's end approached, work on the Military Affairs Committee began to wind down; the idle time resulted in weariness of Washington politics, and Garfield increased his focus on his personal finances.[90]

Garfield partnered with Ralph Plumb in land speculation hoping to become wealthy, but this met with limited success. He joined with the Philadelphia-based Phillips brothers in an oil exploration investment which was moderately profitable.[91] Garfield resumed the practice of law in 1865 as a means to improve his personal finances. His investment efforts took him to Wall Street where, the day after Lincoln's assassination, a riotous crowd led him into an impromptu speech, in part as follows: "Fellow citizens! Clouds and darkness are round about Him! His pavilion is dark waters and thick clouds of the skies! Justice and judgment are the establishment of His throne! Mercy and truth shall go before His face! Fellow citizens! God reigns, and the Government at Washington still lives!" According to witnesses the effect was tremendous and the crowd was immediately calmed. This became one of the most well-known incidents of his career.[92]

Garfield's radicalism moderated after the civil war and Lincoln's assassination, and he assumed a temporary role as peacemaker between Congress and Andrew Johnson. At this time he commented on the readmission of the confederate states: "The burden of proof rests on each of them to show whether it is fit again to enter the federal circle in full communion of privilege. They must give us proof, strong as holy writ, that they have washed their hands and are worthy again to be trusted."[93] When Johnson's veto terminated the Freedmen's Bureau, the President had effectively entrenched himself against Congress, and Garfield rejoined the Radical camp.[94]

With a reduced agenda on the Military Affairs Committee, Garfield was placed on the House Ways and Means Committee, a long-awaited opportunity to focus exclusively on financial and economic issues. He immediately reprised his opposition to the greenback, saying, "any party which commits itself to paper money will go down amid the general disaster, covered with the curses of a ruined people."[95] He called greenbacks "the printed lies of the government"[96] and became obsessed with the morality, as well as the legality, of specie payment, and enforcement of the gold standard. This policy was against his personal interests; his investment profits were dependent upon inflation, the by-product of the greenback. His demand for "hard money" was distinctly deflationary in nature, and was opposed by most businessmen and politicians. For a time, Garfield appeared to be the only Ohio politician to hold this position.[97]

As a proponent of laissez-faire on the economic front, he declared, "the chief duty of the government is to keep the peace and stand out of the sunshine of the people."[98] This view was in stark contrast to his view of the role of government in reconstruction efforts.[99] Another inconsistency in Garfield's laissez-faire philosophy was his position on free trade – he favored the tariff, out of political necessity – when it served to protect his district's products.[100]

Garfield was one of three attorneys who argued for the petitioners in the famous Supreme Court case Ex parte Milligan in 1866. This was, despite many years of practicing law, Garfield's first court appearance. Jeremiah Black had taken him in as a junior partner a year before, and assigned the case to him in light of his highly reputed oratory skills. The petitioners were pro-Confederate northern men who had been found guilty and sentenced to death by a military court for treasonous activities. The case turned on whether the defendants should instead have been tried by a civilian court; Garfield was victorious, and instantly achieved a reputation as a preeminent appellate lawyer.[101]

1866 election and third term[edit]

Despite the allure of a newly lucrative law practice, there was little hesitancy on Garfield's part in deciding to stand for re-election in 1866, due primarily to the urgency presented by Reconstruction. The competition was stiffer, since Garfield now had taken positions on issues which bore defending, such as the draft legislation he supported, tariffs, and his involvement in the Milligan case.[102] As much as anyone, Harmon Austin, a local man of influence, was indispensable to Garfield's success, keeping a finger on the political pulse of the district.[103] The party convention went smoothly in his favor and Garfield won the election with a 5-to-2 margin. At the same time, the Republicans took two-thirds of the national Congressional seats.[104]

Garfield returned to Washington very glum in spite of his success, taking the campaign criticism quite hard. He was disgusted as well at what he thought was insane talk of impeaching President Johnson. With respect to Reconstruction, he thought Congress had been magnanimous in its offers to the South. When the rebels responded to this as a sign of weakness to be exploited by further demands, he was quite prepared to renew his view of them as enemies of the Union. This attitude was popular back home, and initiated talk of a Garfield-for-Governor campaign. Garfield promptly quashed it.[105]

The Congressman expected his new term would bring an appointment as Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, but this was not to be, due largely to his emphatic position in favor of hard money, which did not reflect the House consensus.[106] He was appointed as chairman of the Military Affairs Committee, the primary agenda item there being the reorganization and reduction of the armed forces to put them on a peacetime footing.[107] Garfield at this time endorsed the view that the Senate, via the Tenure of Office Act, had final say on Presidential appointments, a position he would radically change when President himself.[108]

In another reassessment, Garfield supported articles of impeachment against President Andrew Johnson over charges that he violated the Tenure of Office Act by removing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Garfield was absent for the actual vote due to legal work. Support for impeachment was very high, but the result was in doubt due to forebodings about the value of President pro tempore, U.S. Senator Benjamin Wade, a Radical Republican, as successor to President Johnson.[109] He felt the senators were more interested in making speeches than conducting a proper trial. In the end, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, who presided over the trial, was thought to have brought about Johnson's acquittal by the Senate with his statements from the bench. Thus, Garfield's very close friend distinctly became a political adversary, though he persevered with the economic and financial views he had earlier learned from Chase.[110] In 1868 Garfield gave his noted two-hour "Currency" speech in the House, which was widely applauded as his best oratory yet; in it he advocated a gradual resumption of specie payment.[111]

1868 election and fourth term[edit]

Garfield's competition for re-election to a fourth term was weaker than two years prior. The scant opposition there was had few issues with which to take him to task. A futile attempt was made to criticize him as a free trader, when the most that could be said was that he refused to aggressively pursue higher tariffs to protect local products. His nomination went quickly at the party convention; he gave over 60 speeches in his election campaign and was re-elected, with a 2 to 1 margin. Grant won the presidency.[112] At the outset, Garfield's relationship with the newly inaugurated President was cool on both sides; Grant refused a requested post office appointment which Garfield recommended; Garfield, out of loyalty to his army commander, still harbored some resentment for Grant's dismissal of Rosecrans.[113] After six years of housing his family in rented rooms in Washington, Garfield decided to build a house of his own, at a total cost of $13,000. His close army friend, Major David Swaim, loaned him half the money.[114]

While Garfield had by then established himself as a superb orator while managing legislation on the floor of the House, he demonstrated little feel for the mood of the members or ability to control debate on items he brought forward.[115] He continued in this new term to expect the Chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee, but again this was misplaced, due in large part to his shortcomings as a parliamentarian; he was given the chair of the Banking and Currency Committee, but regretted having lost the Military Affairs Chairmanship.[116] One legislative priority of his fourth term was a bill to establish a Department of Education, which succeeded, only to be brought down by poor administration on the part of the first Commissioner of Education, Henry Barnard.[117]

Another pet project of Garfield's this term was a bill to transfer Indian Affairs from the Interior Department to the War Department. His estimate was that the Indians' culture could be more effectively "civilized" with the help of the more structured and disciplined military.[118] The proposal was thought to be ill-conceived from the outset, but Garfield failed to perceive popular opinion.[119] On a positive note in this term, Garfield was appointed chairman of a Subcommittee on the Census; as with other things mathematical, he threw himself into this head and shoulders. The two accomplishments of his work here were to revamp the counting process and to implement a major change in the questionnaire. Garfield showed improvement in handling this on the House floor and it was passed there, although it was stopped in the Senate; ten years later, a similar bill became law, with most of his groundwork in place.[120]

In September 1870 Garfield was chairman of a Congressional committee investigating the Black Friday Gold Panic scandal. The committee investigation into corruption was thorough, but found no indictable offenses. Garfield refused, as irrelevant, a request to subpoena the President's sister, whose husband was allegedly involved in the scandal. Garfield took full advantage of the opportunity to blame the fluctuating greenback for sowing the seeds of greed and speculation that led to the scandal.[121][122] Garfield also pursued his anti-inflationist campaign against the greenback through his work on the bill for a national bank system. He successfully used the bill as a means to reduce the volume of greenbacks in circulation.[123] Garfield's committee investigated President Grant's wife Julia's financial record. Tension remained between President Grant and Rep. Garfield.[124]

1870 election and fifth term[edit]

The election in 1870 brought an increased level of criticism of Garfield for his failure to support higher tariffs, especially from the iron producers in his district. He was denounced by the free traders for what support he did give to the tariff.[125] His opponents accused him of lavish spending in the construction of his new home in Washington, which cost $13,000, while the average cost in the district was $2,000.[126] Nevertheless, his nomination succeeded by acclamation and he won re-election by a margin of just less than 2-to-1.[127]

As in the past, Garfield expected the leadership of the Ways and Means Committee to be his, but again it escaped him, due to opposition from the influential Horace Greeley. He was appointed Chairman of the Appropriations Committee, a position he initially spurned. In time the post commanded his interest and improved his skills as a floor manager.[128] Garfield's outlook for the Republican Party, and the Democrats as well, was very negative at this point. He stated that "the death of both parties is all but certain; the Democrats, because every idea they have brought forward in the past 12 years is dead; and the Republicans, because its ideas have been realized." Nevertheless, when casting his votes, he remained a party regular.[129]

Garfield thought the land grants given to expanding railroads to be an unjust practice; as well, he opposed some monopolistic practices by corporations, as well as the power sought by the workers' unions.[130] By this time Garfield's Reconstruction philosophy had moderated. He hailed the passage of the 15th Amendment as a triumph, and he favored the re-admission of Georgia to the Union as a matter of right, not politics.[131] In 1871, however, Garfield could not support the Ku Klux Klan Act, passed by Congress in 1871, saying "I have never been more perplexed by a piece of legislation". He was torn between his indignation of "these terrorists" and his concern for the freedoms endangered by the power the bill gave to the President to enforce the Act through suspension of habeas corpus.[132]

Garfield supported the proposed establishment of the United States civil service as a means of alleviating the burden of aggressive office seekers upon elected officials. He especially wished to eliminate the common practice whereby government workers, in exchange for their positions, were forced to kick back a percentage of their wages as political contributions.[133]

During this term, discontented with public service, Garfield pursued opportunities in law practice, but declined a partnership offer after being advised his prospective partner was of "intemperate and licentious" reputation.[134] Family life had also increased in importance to Garfield, who said to his wife in 1871, "When you are ill, I am like the inhabitants of a country visited by earthquakes. Like they, I lose all faith in the eternal order and fixedness of things."[135]

1872 election and sixth term[edit]

Garfield was not at all enthused about the re-election of President Grant in 1872—until Horace Greeley emerged as the only potential alternative.[136] In terms of his own re-election, the competition was minimal, if not non-existent. His district was redrawn to his advantage, he was nominated by acclamation at his convention, and he went on to win re-election by a margin of 5-to-2.[136] In that year, he took his first trip west of the Mississippi, on a successful mission to conclude an agreement regarding the relocation of the Flathead Indian tribe.[137]

In 1872, he was one of a number of Congressmen involved in the alleged Crédit Mobilier of America scandal. As part of their expansion efforts, the principals of the Union Pacific Railroad formed Crédit Mobilier of America and issued stock. Congressman Oakes Ames testified Garfield had purchased 10 shares of Crédit Mobiler stock for $1000, received accrued stock interest and $329 (33 per cent) in dividends sometime between December 1867 and June 1868. Ames's credibility suffered greatly due to substantive changes he made in his story under oath, along with very inconsistent and inaccurate records he provided. Garfield biographer Peskin concludes, "From a strictly legal point of view, Ames's testimony was worthless. He repeatedly contradicted himself on important points."[138] According to the New York Times, Garfield had been in debt at the time, having taken out a mortgage on his property.[139] Though Garfield was properly questioned for buying the stock, he had returned it to the seller. The scandal did not imperil his political career severely, though he denied the charges against him rather ineffectively, since the details were convoluted and were never clearly articulated or convincingly proven.[140]

In 1873, Garfield appealed to President Grant to appoint Justice Noah H. Swayne as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. The previous Chief Justice, Salmon P. Chase, had died in office May 7, 1873. Pres. Grant, however, appointed Morrison R. Waite.[141]

Later in this term, Garfield found himself in the position of having to vote for his Appropriation Committee's bill, which included a provision to increase Congressional and Presidential salaries, something he opposed. This controversial act, known as the "Salary Grab", was signed into law in March 1873. In June congressional supporters of the law received vitriolic response from the press and the voting public.[142] This vote was the source of an increased degree of criticism of Garfield, though he was reappointed Chairman of the Appropriations Committee and placed on the Rules Committee. The vote did, however, give rise to stiffer competition in the next election.[143] He returned his own salary increase to the U.S. Treasury.

No comments:

Post a Comment