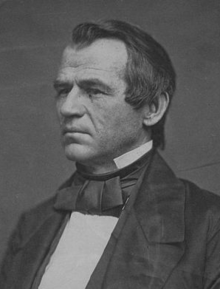

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875) was the 17th President of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. Johnson became president as Abraham Lincoln's vice president at the time of Lincoln's assassination. A Democrat who ran with Lincoln on the National Union ticket, Johnson came to office as the Civil War concluded. The new president favored quick restoration of the seceded states to the Union. His plans did not give protection to the former slaves, and he came into conflict with the Republican-dominated Congress, culminating inhis impeachment by the House of Representatives. The first American president to be impeached, he was acquitted in the Senate by one vote.

Johnson was born in poverty in Raleigh, North Carolina. Apprenticed as a tailor, he worked in several frontier towns before settling in Greeneville, Tennessee. He served as alderman and mayor there before being elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1835. After brief service in the Tennessee Senate, Johnson was elected to the federal House of Representatives in 1843, where he served five two-year terms. He became Governor of Tennessee for four years, and was elected by the legislature to the Senate in 1857. In his congressional service, he sought passage of the Homestead Bill, which was enacted soon after he left his Senate seat in 1862.

As Southern states, including Tennessee, seceded to form the Confederate States of America, Johnson remained firmly with the Union. In 1862, Lincoln appointed him as military governor of Tennessee after it had been retaken. In 1864, Johnson, as a War Democrat and Southern Unionist, was a logical choice as running mate for Lincoln, who wished to send a message of national unity in his re-election campaign; their ticket easily won. Johnson was sworn in as vice president in March 1865, giving a rambling and possibly drunken speech, and he secluded himself to avoid public ridicule. Six weeks later, the assassination of Lincoln made him president.

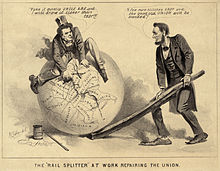

Johnson implemented his own form of Presidential Reconstruction – a series of proclamations directing the seceded states to hold conventions and elections to re-form their civil governments. When Southern states returned many of their old leaders, and passed Black Codes to deprive the freedmen of many civil liberties, Congress refused to seat legislators from those states and advanced legislation to overrule the Southern actions. Johnson vetoed their bills, and Congress overrode him, setting a pattern for the remainder of his presidency. Johnson opposed theFourteenth Amendment, which gave citizenship to African-Americans. As the conflict between the branches of government grew, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, restricting Johnson in firing Cabinet officials. When he persisted in trying to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, he was impeached by the House of Representatives, and narrowly avoided conviction in the Senate and removal from office. Returning to Tennessee after his presidency, Johnson sought political vindication, and gained it in his eyes when he was elected to the Senate again in 1875 (the only former president to serve there), just months before his death. Although Johnson's ranking has fluctuated over time, he is generally considered among the worst American presidents for his opposition to federally guaranteed rights for African Americans.

Contents

[show]Early life and career[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina on December 29, 1808, to Jacob Johnson (1778–1812) and Mary ("Polly") McDonough (1783–1856), a laundress. He had a brother William, four years his elder, and an older sister Elizabeth, who died in childhood. (Being born in a log cabinwas a political asset in the 19th century, and in the years to come Johnson would not hesitate to remind voters of his humble birth.)[2] Jacob Johnson was a poor man, as was his father, William, but became town constable of Raleigh before marrying and starting a family. He died of an apparent heart attack while ringing the town bell, shortly after rescuing three drowning men when Andrew was three.[3] Polly Johnson had worked as a washerwoman; she continued in that trade as the sole support of her children. At the time, her occupation was considered less than respectable as it often took her into others' homes unaccompanied; the Johnsons were considered white trash, and there were rumors that Andrew, who did not resemble his siblings, was fathered by another man. Eventually, Polly Johnson married Turner Doughtry, who was also poor.[4]

Polly Doughtry apprenticed her elder son, William, to a tailor, James Selby. Andrew followed his brother as an apprentice in Selby's shop at the age of ten; he was legally bound to serve until his 21st birthday. Selby does not appear to have had any great influence on the future president. The apprentice was boarded with his mother for part of his service; one of Selby's employees was detailed to teach him rudimentary literacy skills.[5]This minimal education was augmented by citizens who came to Selby's shop to read to the tailors as they worked; even before he was an apprentice, young Andrew came to listen. These readings began a lifelong love of learning for the boy; his biographer, Annette Gordon-Reed, suggests that Johnson, who would be acclaimed as a public speaker, learned the basics of that art as he threaded needles and cut cloth.[6]

Andrew Johnson was not happy at James Selby's, and at about age 15, ran away with his brother. Selby responded by placing an advertisement in the paper, as customary for masters seeking missing apprentices, "Ten Dollars Reward. Ran away from the subscriber, two apprentice boys, legally bound, named William and Andrew Johnson ... [payment] to any person who will deliver said apprentices to me in Raleigh, or I will give the above reward for Andrew Johnson alone."[7] The boys went to Carthage, North Carolina, where Andrew Johnson worked as a tailor for several months. Fearing he would be taken and returned to Raleigh, Andrew moved on to Laurens, South Carolina. There, he found work in his craft, and met his first love, Mary Wood, for whom he made a quilt. After his marriage proposal to her was rejected, Johnson returned to Raleigh, hoping to buy out his apprenticeship, but he could not come to terms with Selby. Then, like many others in the late 1820s, he journeyed west.[8][9]

Move to Tennessee[edit]

Johnson left North Carolina for Tennessee, traveling mostly on foot. After a brief period in Knoxville, he moved to Mooresville, Alabama.[8][10] He then worked as a tailor in Columbia, Tennessee, but was called back to Raleigh by his mother and stepfather, who saw limited opportunities there and who wished to emigrate west. Johnson and his party traveled through theBlue Ridge Mountains to Greeneville, Tennessee. Andrew Johnson fell in love with the town at first sight, and when he became prosperous purchased the land where he had first camped and planted a tree in commemoration.[11]

In Greeneville, Johnson established a successful tailoring business in the front of his home. In 1827, at the age of 18, he married 16-year-old Eliza McCardle, the daughter of a local shoemaker. The pair were married by Justice of the Peace Mordecai Lincoln, first cousin of Thomas Lincoln, whose son would become president. The Johnsons were married for almost 50 years and had five children: Martha (1828), Charles (1830), Mary (1832), Robert (1834), and Andrew Jr. (1852). Though she suffered from consumption, Eliza supported her husband's endeavors. She taught him mathematics skills and tutored him to improve his writing.[12][13] Shy and retiring by nature, Eliza Johnson usually remained in Greeneville during Johnson's political rise. She was not often seen during her husband's presidency; their daughter Martha usually served as official hostess.[14]

Johnson's tailoring business prospered during the early years of the marriage, enabling him to hire help and giving him the funds to invest profitably in real estate.[15] He later boasted of his talents as a tailor, "my work never ripped or gave way."[16] He was a voracious reader. Books about famous orators aroused his interest in political dialogue, and he had private debates with customers with opposing views on issues of the day. He also took part in debates at Greeneville College.[17]

Political rise[edit]

Tennessee politician[edit]

Johnson helped organize a mechanics' (working men's) ticket in the 1829 Greeneville municipal election. He was elected town alderman, along with his friends Blackston McDannel and Mordecai Lincoln.[18][19] Following the 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion, a state convention was called to pass a new constitution, including provisions to disenfranchise free people of color. The convention also wanted to reform real estate tax rates, and provide ways of funding improvements to Tennessee's infrastructure. The constitution was submitted for a public vote, and Johnson spoke widely for its adoption; the successful campaign provided him with statewide exposure. On January 4, 1834, his fellow aldermen elected him mayor of Greeneville.[20][21]

In 1835, Johnson made a bid for election to the "floater" seat which Greene County shared with neighboring Washington County in the Tennessee House of Representatives. According to his biographer, Hans L. Trefousse, Johnson "demolished" the opposition in debate and won the election with almost a two to one margin.[22][23] Soon after taking his seat, Johnson purchased his first slave, Dolly, aged 14. Dolly had three children over the years. Johnson had the reputation of treating his slaves kindly, but the fact that Dolly was dark-skinned, and her offspring much lighter, led to speculation both during and after his lifetime that he was the father.[24] During his Greeneville days, Johnson joined the Tennessee Militia as a member of the 90th Regiment. He attained the rank of colonel, though while an enrolled member, Johnson was fined for an unknown offense.[25] Afterwards, he was often addressed or referred to by his rank.

In his first term in the legislature, which met in the state capital of Nashville, Johnson did not consistently vote with either the Democratic or the newly formed Whig Party, though he revered President Andrew Jackson, a Democrat and Tennessean. The major parties were still determining their core values and policy proposals, with the party system in a state of flux. The Whig Party had organized in opposition to Jackson, fearing the concentration of power in the Executive Branch of the government; Johnson differed from the Whigs as he opposed more than minimal government spending and spoke against aid for the railroads, while his constituents hoped for improvements in transportation. After Brookins Campbell and the Whigs defeated Johnson for re-election in 1837, Johnson would not lose another race for thirty years. In 1839, he sought to regain his seat, initially as a Whig, but when another candidate sought the Whig nomination, he ran as a Democrat and was elected. From that time he supported the Democratic party and built a powerful political machine in Greene County.[26][27] Johnson became a strong advocate of the Democratic Party, noted for his oratory, and in an era when public speaking both informed the public and entertained it, people flocked to hear him.[28]

In 1840, Johnson was selected as a presidential elector for Tennessee, giving him more statewide publicity. Although Democratic President Martin Van Buren was defeated by former Ohio senator William Henry Harrison, Johnson was instrumental in keeping Tennessee and Greene County in the Democratic column.[29] He was elected to the Tennessee Senate in 1841, where he served a two-year term.[30] He had achieved financial success in his tailoring business, but sold it to concentrate on politics. He had also acquired additional real estate, including a larger home and a farm (where his mother and stepfather took residence), and among his assets numbered eight or nine slaves.[31]

Congressman (1843–1853)[edit]

Having served in both houses of the legislature, Johnson saw election to Congress as the next step in his political career. He engaged in a number of political maneuvers to gain Democratic support, including the displacement of the Whig postmaster in Greeneville, and defeated Jonesville lawyer John A. Aiken by 5,495 votes to 4,892.[32][33] In Washington, he joined a new Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. Johnson advocated for the interests of the poor, maintained an anti-abolitionist stance, argued for only limited spending by the government and opposed protective tariffs.[34] With Eliza remaining in Greeneville, Congressman Johnson shunned social functions in favor of study in the Library of Congress.[35] Although a fellow Tennessee Democrat, James K. Polk, was elected president in 1844, and Johnson had campaigned for him, the two men had difficult relations, and President Polk refused some of his patronage suggestions.[36]

Johnson believed, as did many Southern Democrats, that the Constitution protected private property, including slaves, and thus prohibited the federal and state governments from abolishing slavery.[37] He won a second term in 1845 against Wiliam G. Brownlow, presenting himself as the defender of the poor against the aristocracy. In his second term, Johnson supported the Polk administration's decision to fight the Mexican War, seen by some Northerners as an attempt to gain territory to expand slavery westward, and opposed the Wilmot Proviso, a proposal to ban slavery in any territory gained from Mexico. He introduced for the first time his Homestead Bill, to grant 160 acres (65 ha) to people willing to settle the land and gain title to it.[38][39] This issue was especially important to Johnson because of his own humble beginnings.[38][40]

In the presidential election of 1848, the Democrats split over the slavery issue, and abolitionists formed the Free Soil Party, with former president Van Buren as their nominee. Johnson supported the Democratic candidate, former Michigan senator Lewis Cass. With the party split, Whig nominee General Zachary Taylor was easily victorious, and carried Tennessee.[41] Johnson's relations with Polk remained poor; the President recorded of his final New Year's reception in 1849 that

Among the visitors I observed in the crowd today was Hon. Andrew Johnson of the Ho. Repts. [House of Representatives] Though he represents a Democratic District in Tennessee (my own State) this is the first time I have seen him during the present session of Congress. Professing to be a Democrat, he has been politically, if not personally hostile to me during my whole term. He is very vindictive and perverse in his temper and conduct. If he had the manliness and independence to declare his opposition openly, he knows he could not be elected by his constituents. I am not aware that I have ever given him cause for offense.[42]

Johnson, due to national interest in new railroad construction and in response to the need for better transportation in his own district, also supported government assistance for the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad.[43]

In his campaign for a fourth term, Johnson concentrated on three issues: slavery, homesteads and judicial elections. He defeated his opponent, Nathaniel G. Taylor, in August 1849, with a greater margin of victory than in previous campaigns. When the House convened in December, the party division caused by the Free Soil Party precluded the formation of the majority needed to elect a Speaker. Johnson proposed adoption of a rule allowing election of a Speaker by a plurality; some weeks later others took up a similar proposal, and Democrat Howell Cobb was elected.[44]

Once the Speaker election had concluded and Congress was ready to conduct legislative business, the issue of slavery took center stage. Northerners sought to admit California, a free state, to the Union. Kentucky's Henry Clay introduced in the Senate a series of resolutions, the Compromise of 1850, to admit California and pass legislation sought by each side. Johnson voted for all the provisions except for the abolition of slavery in the nation's capital.[45] He pressed resolutions for constitutional amendments to provide for popular election of senators (then elected by state legislatures) and of the president (chosen by the Electoral College), and limiting the tenure of federal judges to 12 years. These were all defeated.[46]

A group of Democrats nominated Landon Carter Haynes to oppose Johnson as he sought a fifth term; the Whigs were so pleased with the internecine battle among the Democrats in the general election that they did not nominate a candidate of their own. The campaign included fierce debates: Johnson's main issue was the passage of the Homestead Bill; Haynes contended it would facilitate abolition. Johnson won the election by more than 1600 votes.[46] Though he was not enamored of the party's presidential nominee in 1852, former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce, Johnson campaigned for him. Pierce was elected, but he failed to carry Tennessee.[47] In 1852, Johnson managed to get the House to pass his Homestead Bill, but it failed in the Senate.[48] The Whigs had gained control of the Tennessee legislature, and, under the leadership of Gustavus Henry, redrew the boundaries of Johnson's First District to make it a safe seat for their party. The Nashville Union termed this "Henry-mandering";[a][49] lamented Johnson, "I have no political future."[50]

Governor of Tennessee (1853–1857)[edit]

If Johnson considered retiring from politics upon deciding not to seek re-election, he soon changed his mind.[51] The congressman's political friends began to maneuver to get him the nomination for governor. The Democratic convention unanimously named him, though some party members were not happy at his selection. The Whigs had won the past two gubernatorial elections, and still controlled the legislature.[52] That party nominated Henry, making the "Henry-mandering" of the First District an immediate issue.[52] The two men debated in county seats the length of Tennessee before the meetings were called off two weeks before the August 1853 election due to illness in Henry's family.[51][53]Johnson won the election by 63,413 votes to 61,163; some votes for him were cast in return for his promise to support Whig Nathaniel Taylor for his old seat in Congress.[54][55]

Tennessee's governor had little power—Johnson could propose legislation but not veto it, and most appointments were made by the Whig-controlled legislature. Nevertheless, the office was a bully pulpit that allowed him to publicize himself and his political views.[56] He succeeded in getting the appointments he wanted in return for his endorsement of John Bell, a Whig, for one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. In his first biennial speech, Johnson urged simplification of the state judicial system, abolishment of the Bank of Tennessee and establishment of an agency to provide uniformity in weights and measures; the last was passed. Johnson was critical of the Tennessee common school system and suggested funding be increased via taxes, either statewide or county by county—a mixture of the two was passed.[57]

Although the Whig Party was on its final decline nationally, it remained strong in Tennessee, and the outlook for Democrats there in 1855 was poor. Feeling that re-election as governor was necessary to give him a chance at the higher offices he sought, Johnson agreed to make the run. Meredith P. Gentry received the Whig nomination. A series of more than a dozen vitriolic debates ensued.[58] The issues in the campaign were slavery, the prohibition of alcohol, and the nativist positions of the Know Nothing Party. Johnson favored the first, but opposed the others. Gentry was more equivocal on the alcohol question, and had gained the support of the Know Nothings, a group Johnson portrayed as a secret society.[59] Johnson was unexpectedly victorious, albeit with a narrower margin than in 1853.[58]

When the presidential election of 1856 approached, Johnson hoped to be nominated; some Tennessee county conventions designated him a favorite son. His position that the best interests of the Union were served by slavery in some areas made him a practical compromise candidate for president. He was never a major contender; the nomination fell to former Pennsylvania senator James Buchanan. Though he was not impressed by either, Johnson campaigned for Buchanan and his running mate, former Kentucky representative John C. Breckenridge, who were elected.[60]

Johnson decided not to seek a third term as governor, with an eye towards election to the U.S. Senate. In 1857, while returning from Washington, his train derailed, causing serious damage to his right arm. This injury would trouble him in the years to come.[61]

United States Senator[edit]

Homestead Bill advocate[edit]

The victors in the 1857 state legislative campaign would, once they convened in October, elect a United States Senator. Former Whig governor William B. Campbell wrote to his uncle, "The great anxiety of the Whigs is to elect a majority in the legislature so as to defeat Andrew Johnson for senator. Should the Democrats have the majority, he will certainly be their choice, and there is no man living to whom the Americans[b] and Whigs have as much antipathy as Johnson."[62] The governor spoke widely in the campaign, and his party won the gubernatorial race and control of the legislature.[63] Johnson's final address as governor gave him the chance to influence his electors, and he made proposals popular among Democrats. Two days later the legislature elected him to the Senate. The opposition was appalled, with the Richmond Whig newspaper referring to him as "the vilest radical and most unscrupulous demagogue in the Union."[64]

Johnson gained high office due to his proven record as a man popular among the small farmers and self-employed tradesmen who made up much of Tennessee's electorate. He called them the "plebians"; he was less popular among the planters and lawyers who led the state Democratic Party, but none could match him as a vote-getter. After his death, one Tennessee voter wrote of him, "Johnson was always the same to everyone ... the honors heaped upon him did not make him forget to be kind to the humblest citizen."[65] Always seen in impeccably tailored clothing, he cut an impressive figure,[66] and had the stamina to endure lengthy campaigns with daily travel over bad roads leading to another speech or debate. Mostly denied the party's machinery, he relied on a network of friends, advisers, and contacts.[50] One friend, Hugh Douglas, stated in a letter to him, "you have been in the way of our would be great men for a long time. At heart many of us never wanted you to be Governor only none of the rest of us Could have been elected at the time and we only wanted to use you. Then we did not want you to go to the Senate but the people would send you."[67]

The new senator took his seat when Congress convened in December 1857 (the term of his predecessor, James C. Jones, had expired in March). He came to Washington as usual without his wife and family; Eliza would visit Washington only once during Johnson's first time as senator, in 1860. Johnson immediately set about introducing the Homestead Bill in the Senate, but as most senators who supported it were Northern (many associated with the newly founded Republican Party), the matter became caught up in suspicions over the slavery issue. Southern senators felt that those who took advantage of the provisions of the Homestead Bill were more likely to be Northern non-slaveholders. The issue of slavery had been complicated by the Supreme Court's ruling earlier in the year in Dred Scott v. Sandford that slavery could not be prohibited in the territories. Johnson, a slaveholding senator from a Southern state, made a major speech in the Senate the following May in an attempt to convince his colleagues that the Homestead Bill and slavery were not incompatible. Nevertheless, Southern opposition was key to defeating the legislation, 30–22.[68][69] In 1859, it failed on a procedural vote when Vice President Breckinridge broke a tie against the bill, and in 1860, a watered-down version passed both houses, only to be vetoed by Buchanan at the urging of Southerners.[70]Johnson continued his opposition to spending, chairing a committee to control it.

He argued against funding to build Washington, D.C.'s infrastructure, stating that it was unfair to expect state citizens to pay for the city's streets, even if it was the seat of government. He opposed spending money for troops to put downthe revolt by the Mormons in Utah Territory, arguing for temporary volunteers as the United States should not have a standing army.[71]

Secession crisis[edit]

In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown and sympathizers raided the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (today West Virginia). Tensions in Washington between pro- and anti-slavery forces increased greatly. Johnson gave a major speech in the Senate in December, decrying Northerners who would endanger the Union by seeking to outlaw slavery. The Tennessee senator stated that "all men are created equal" from the Declaration of Independence did not apply to African-Americans, since the Constitution of Illinois contained that phrase—and that document barred voting by African-Americans.[72][73]

Johnson hoped that he would be a compromise candidate for the 1860 presidential nomination as the Democratic Party tore itself apart over the slavery question. Busy with the Homestead Bill during the 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina, he sent two of his sons and his chief political adviser to represent his interest in the backroom dealmaking. The convention deadlocked, with no candidate able to gain the required two-thirds vote, but the sides were too far apart to consider Johnson as a compromise. The party split, with Northerners backing Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas while Southerners, including Johnson, supported Vice President Breckinridge for president. With former Tennessee senator John Bell running a fourth-party candidacy and further dividing the vote, the Republican Party elected its first president, former Illinois representative Abraham Lincoln. The election of Lincoln, known to be against slavery, was unacceptable to many in the South. Although secession from the Union had not been an issue in the campaign, talk of it began in the Southern states.[74][75]

Johnson took to the Senate floor after the election, giving a speech well received in the North, "I will not give up this government ... No; I intend to stand by it ... and I invite every man who is a patriot to ... rally around the altar of our common country ... and swear by our God, and all that is sacred and holy, that the Constitution shall be saved, and the Union preserved."[76][77] As Southern senators announced they would resign if their states seceded, he reminded Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis that if Southerners would only hold to their seats, the Democrats would control the Senate, and could defend the South's interests against any infringement by Lincoln.[78] Gordon-Reed points out that while Johnson's belief in an indissoluble Union was sincere, he had alienated Southern leaders, including Davis, who would soon be the president of the Confederate States of America, formed by the seceding states. If the Tennessean had backed the Confederacy, he would have had small influence in its government.[79]

Johnson returned home when his state took up the issue of secession. His successor as governor, Isham G. Harris, and the legislature, organized a referendum on whether to have a constitutional convention to authorize secession; when that failed, they put the question of leaving the Union to a popular vote. Despite threats on Johnson's life, and actual assaults, he campaigned against both questions, sometimes speaking with a gun on the lectern before him. Although Johnson's eastern region of Tennessee was against secession, the second referendum passed, and in June 1861, Tennessee joined the Confederacy. Believing he would be killed if he stayed, the senator fled the state through the Cumberland Gap, where his party was fired upon; he left his wife and family in Greeneville.[80][81]

As the only member from a seceded state to remain in the Senate and the most prominent Southern Unionist, he had Lincoln's ear in the early months of the war.[82] With most of Tennessee in Confederate hands, Johnson spent congressional recesses in Kentucky and Ohio, trying in vain to convince any Union commander who would listen to conduct an operation into East Tennessee.[83]

Military Governor of Tennessee[edit]

Johnson's first tenure in the Senate came to a conclusion in March 1862 when Lincoln appointed him military governor of Tennessee. Much of the central and western portions of that seceded state had been recovered. Although some argued that civil government should simply resume once the Confederates were put down in an area, Lincoln chose to use his power as commander in chief to appoint military governors over Union-controlled Southern areas.[84] The Senate quickly confirmed Johnson's nomination along with the rank of brigadier general.[85] In response, the Confederates confiscated his land, took away his slaves, and made his home into a military hospital.[86] Later in 1862, after his departure from the Senate and in the absence of most Southern legislators, the Homestead Act was finally enacted; it, along with legislation for land grant colleges and for the transcontinental railroad, has been credited with opening the American West to settlement.[87]

As military governor, Johnson sought to eliminate rebel influences in the state, demanding loyalty oaths from public officials, and shutting down newspapers run by Confederate sympathizers. At that time, much of eastern Tennessee remained in rebel hands, and the ebb and flow of war through 1862 sometimes brought Confederate control close to Nashville. The Confederates did allow his wife and family to pass through the lines to him.[88][89] Johnson undertook the defense of Nashville as best he could; the city was continually harassed with cavalry raids led by General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Relief from Union regulars did not come until William S. Rosecrans defeated the Confederates atMurfreesboro at the start of 1863. Much of eastern Tennessee was retaken later that year.[90]

When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, freeing the slaves in rebel-controlled areas, he exempted Tennessee at Johnson's request. The document increased the debate over what should happen to the slaves after the war—not all Unionists supported abolition. Johnson decided that slavery had to end, stating, "If the institution of slavery ... seeks to overthrow it [the Government], then the Government has a clear right to destroy it".[91]He reluctantly supported efforts to recruit former slaves for the Union Army, feeling it more appropriate that African-Americans should perform menial tasks and free up whites to fight.[92] Nevertheless, he succeeded in enlisting 20,000 black troops for the Union.[93]

Vice President[edit]

Main article: United States presidential election, 1864

In 1860, Lincoln's running mate had been Maine Senator Hannibal Hamlin. Vice President Hamlin had served competently, was in good health, and was willing to run. Nevertheless, Johnson emerged as running mate for Lincoln's re-election bid in 1864.[94]

Lincoln considered several War Democrats for the ticket in 1864, and sent an agent to sound out General Benjamin Butler as a possible running mate. In May 1864, the President dispatched General Daniel Sickles to Nashville on a fact-finding mission. Although Sickles denied he was there either to investigate or interview the military governor, Johnson biographer Hans L. Trefousse believes Sickles's trip was connected to Johnson's subsequent nomination for vice president.[94] According to historian Albert Castel in his account of Johnson's presidency, Lincoln was impressed by Johnson's administration of Tennessee.[88] Gordon-Reed points out that while the Lincoln-Hamlin ticket might have been considered geographically balanced in 1860, "having Johnson, the southern War Democrat, on the ticket sent the right message about the folly of secession and the continuing capacity for union within the country."[95] Another factor was the desire of Secretary of State William Seward to frustrate the vice-presidential candidacy of his fellow New Yorker, former senator Daniel S. Dickinson, a War Democrat, as Seward would probably have had to yield his place if another New Yorker became vice president. Johnson, once he was told by reporters the likely purpose of Sickles' visit, was active on his own behalf, giving speeches and having his political friends work behind the scenes to boost his candidacy.[96]

To sound a theme of unity, Lincoln in 1864 ran under the banner of the National Union Party, rather than the Republicans.[95] At the party's convention in Baltimore in June, Lincoln was easily nominated, although there had been some talk of replacing him with a Cabinet officer or one of the more successful generals. After the convention backed Lincoln, former Secretary of War Simon Cameron offered a resolution to nominate Hamlin, but it was defeated. Johnson was nominated for vice president by C.M. Allen of Indiana with an Iowa delegate as seconder. On the first ballot, Johnson led with 200 votes to 150 for Hamlin and 108 for Dickinson. On the second ballot, Kentucky switched to vote for Johnson, beginning a stampede. Johnson was named on the second ballot with 491 votes to Hamlin's 17 and eight for Dickinson; the nomination was made unanimous. Lincoln expressed pleasure at the result, "Andy Johnson, I think, is a good man."[97] When word reached Nashville, a crowd assembled and the military governor obliged with a speech contending his selection as a Southerner meant that the rebel states had not actually left the Union.[97]

Although it was unusual at the time for a national candidate to actively campaign, Johnson gave a number of speeches in Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana. He also sought to boost his chances in Tennessee while re-establishing civil government by making the loyalty oath even more restrictive, in that voters would now have to swear they opposed making a settlement with the Confederacy. The Democratic candidate for president, George McClellan, hoped to avoid additional bloodshed by negotiation, and so the stricter loyalty oath effectively disenfranchised his supporters. Lincoln declined to override Johnson, and their ticket took the state by 25,000 votes. Congress refused to count Tennessee's electoral votes, but Lincoln and Johnson did not need them, having won in most states that had voted, and easily secured the election.[98]

Now Vice President-elect, Johnson was anxious to complete the work of re-establishing civilian government in Tennessee, although the timetable for the election of a new governor did not allow it to take place until after Inauguration Day, March 4. He hoped to remain in Nashville to complete his task, but was told by Lincoln's advisers that he could not stay, but would be sworn in with Lincoln. In these months, Union troops finished the retaking of eastern Tennessee, including Greeneville. Just before his departure, the voters of Tennessee ratified a new constitution, abolishing slavery, on February 22, 1865. One of Johnson's final acts as military governor was to certify the results.[99]

Johnson traveled to Washington to be sworn in, although according to Gordon-Reed, "in light of what happened on March 4, 1865, it might have been better if Johnson had stayed in Nashville."[100] He may have been ill; Castel cited typhoid fever,[88] though Gordon-Reed notes that there is no independent evidence for that diagnosis.[100] On the evening of March 3, Johnson attended a party in his honor; he drank heavily. Hung over the following morning at the Capitol, he asked Vice President Hamlin for some whiskey. Hamlin produced a bottle, and Johnson took two stiff drinks, stating "I need all the strength for the occasion I can have." In the Senate Chamber, Johnson delivered a rambling address as Lincoln, the Congress, and dignitaries looked on. Almost incoherent at times, he finally meandered to a halt, whereupon Hamlin hastily swore him in as vice president.[101] Lincoln, who had watched sadly during the debacle, was sworn in, and delivered his acclaimed Second Inaugural Address.[102]

In the weeks after the inauguration, Johnson only presided over the Senate briefly, and hid from public ridicule at the Maryland home of a friend, Francis Preston Blair. When he did return to Washington, it was with the intent of leaving for Tennessee to re-establish his family in Greeneville. Instead, he remained after word came that General Ulysses S. Grant had captured the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, presaging the end of the war.[103] Lincoln stated, in response to criticism of Johnson's behavior, that "I have known Andy Johnson for many years; he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared; Andy ain't a drunkard."[104]

Presidency (1865–1869)[edit]

Accession[edit]

Main article: Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On the afternoon of April 14, 1865, Lincoln and Johnson met for the first time since the inauguration. Trefousse states that Johnson wanted to "induce Lincoln not to be too lenient with traitors"; Gordon-Reed agrees.[105][106]

That night, President Lincoln was shot and mortally wounded by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer. The shooting of the President was part of a conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln, Johnson, and Seward the same night. Seward barely survived his wounds, while Johnson escaped attack as his would-be assassin, George Atzerodt, got drunk instead of killing the vice president. Leonard J. Farwell, a fellow boarder at the Kirkwood House, awoke Johnson with news of Lincoln's shooting at Ford's Theater. Johnson rushed to the President's deathbed, where he remained a short time, on his return promising, "They shall suffer for this. They shall suffer for this."[107] Lincoln died at 7:22 am the next morning; Johnson's swearing in occurred between 10 and 11 am with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding in the presence of most of the Cabinet. Johnson's demeanor was described by the newspapers as "solemn and dignified".[108] Some Cabinet members had last seen Johnson, apparently drunk, at the inauguration.[109] At noon, Johnson conducted his first Cabinet meeting in the Treasury Secretary's office, and asked all members to remain in their positions.[110]

The events of the assassination resulted in speculation, then and subsequently, concerning Johnson and what the conspirators might have intended for him. In the vain hope of having his life spared, after his capture, Atzerodt spoke much about the conspiracy, but did not say anything to indicate that the plotted assassination of Johnson was merely a ruse. Conspiracy theorists point to the fact that on the day of the assassination, Booth came to the Kirkwood House and left one of his cards. This object was received by Johnson's private secretary, William A. Browning, with an inscription, "Are you at home? Don't wish to disturb you. J. Wilkes Booth."[111]

Johnson presided with dignity over Lincoln's funeral ceremonies in Washington, before the leader's body was sent home to Springfield, Illinois, for burial.[112] Shortly after Lincoln's death, Union General William T. Sherman reported he had, without consulting Washington, reached an armistice agreement with Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston for the surrender of Confederate forces in North Carolina in exchange for the existing state government remaining in power, with private property rights to be respected. This did not even acknowledge the freedom of those in slavery. This was not acceptable to Johnson or the Cabinet who sent word for Sherman to secure the surrender without making political deals, which he did. Further, Johnson placed a $100,000 bounty on Confederate President Davis, then a fugitive, which gave him the reputation of a man who would be tough on the South. More controversially, he permitted the execution of Mary Surratt, for her part in Lincoln's assassination who was executed with three others, including Atzerodt, on July 7, 1865.[113]

No comments:

Post a Comment