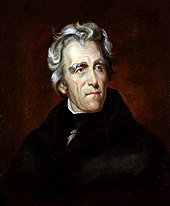

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh President of the United States (1829–1837). Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend (1814), and the British at the Battle of New Orleans (1815). A polarizing figure who dominated the Second Party System in the 1820s and 1830s, as president he dismantled the Second Bank of the United States and initiated forced relocation and resettlement of Native American tribes from the Southeast to west of the Mississippi River with the Indian Removal Act (1830). His enthusiastic followers created the modern Democratic Party. The 1830–1850 period later became known as the era of Jacksonian democracy.[1]

Jackson was nicknamed Old Hickory because of his toughness and aggressive personality; he fought in duels, some fatal to his opponents.[2] He was a wealthy slaveholder. He fought politically against what he denounced as a closed, undemocratic aristocracy, adding to his appeal to common citizens. He expanded the spoils system during his presidency to strengthen his political base.

Elected president in 1828, Jackson supported a small and limited federal government. He strengthened the power of the presidency, which he saw as spokesman for the entire population, as opposed to Congressmen from a specific small district. He was supportive of states' rights, but during the Nullification Crisis, declared that states do not have the right to nullify federal laws. Strongly against the Second Bank of the United States, he vetoed the renewal of its charter and ensured its collapse. Whigs and moralists denounced his aggressive enforcement of the Indian Removal Act, which resulted in the forced relocation of thousands of Native Americans to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Historians acknowledge his protection of popular democracy and individual liberty for American citizens, but criticize his support for slavery and his role in Indian removal.[3][4]

Contents

[show]Early life and education

Jackson was born on March 15, 1767. His parents were Scots-Irish colonists Andrew and Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, Presbyterians who had emigrated from Ireland two years earlier.[5][6]Jackson's father was born in Carrickfergus, County Antrim, in current-day Northern Ireland, around 1738.[7] Jackson's parents lived in the village of Boneybefore, also in County Antrim.

When they emigrated to America in 1765, Jackson's parents probably landed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. They would have traveled overland down through the Appalachian Mountains to the Scots-Irish community in the Waxhaws region, straddling the border between North and South Carolina.[8] They brought two children from Ireland, Hugh (born 1763) and Robert (born 1764).

Jackson's father died in an accident in February 1767, at the age of 29, three weeks before his son Andrew was born in the Waxhaws area. His exact birth site is unclear because he was born about the time his mother was making a difficult trip home from burying Jackson's father. The area was so remote that the border between North and South Carolina had not been officially surveyed.[9]

In 1824, Jackson wrote a letter saying that he was born at an uncle's plantation in Lancaster County, South Carolina. But he may have claimed to be a South Carolinian because the state was considering nullification of the Tariff of 1824, which Jackson opposed. In the mid-1850s, second-hand evidence indicated that he may have been born at a different uncle's home in North Carolina.[9]

Jackson received a sporadic education in the local "old-field" school.[10] In 1781, he worked for a time in a saddle-maker's shop.[11] Later, he taught school and studied law in Salisbury, North Carolina. In 1787, he was admitted to the bar, and moved to Jonesborough, in what was then the Western District of North Carolina. This area later became the Southwest Territory (1790), the precursor to the state of Tennessee.

Early military service

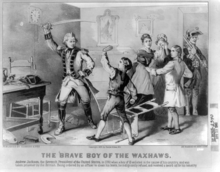

During the American Revolutionary War, Jackson, at age thirteen, joined a local militia as a courier.[12] His eldest brother, Hugh, died from heat exhaustion during the Battle of Stono Ferry, on June 20, 1779. Jackson and his brother Robert were captured by the British and held as prisoners; they nearly starved to death in captivity. When Jackson refused to clean the boots of a British officer, the officer slashed at the youth with a sword, leaving Jackson with scars on his left hand and head, as well as an intense hatred for the British.[13] While imprisoned, the brothers contractedsmallpox.

Robert Jackson died on April 27, 1781, a few days after their mother Elizabeth secured the brothers' release. After being assured Andrew would recover, Elizabeth Jackson volunteered to nurse prisoners of war on board two ships in Charleston harbor, where there had been an outbreak ofcholera. She died from the disease in November 1781, and was buried in an unmarked grave. Jackson became an orphan at age 14.[13] Following the deaths of his brothers and mother during the war, Jackson blamed the British for his losses.

Legal and political career

Jackson began his legal career in Jonesborough, now northeastern Tennessee. Though his legal education was scanty, he knew enough to be acountry lawyer on the frontier. Since he was not from a distinguished family, he had to make his career by his own merits; soon he began to prosper in the rough-and-tumble world of frontier law. Most of the actions grew out of disputed land-claims, or from assault and battery. In 1788, he was appointed Solicitor (prosecutor) of the Western District and held the same position in the government of the Territory South of the River Ohio after 1791.

Jackson was elected as a delegate to the Tennessee constitutional convention in 1796. When Tennessee achieved statehood that year, Jackson was elected its U.S. Representative. The following year, he was elected U.S. Senator as a Democratic-Republican, but he resigned within a year. (His return to the U.S. Senate in 1823, after 24 years, 11 months, 3 days out of office, marks the second longest gap in service to the chamber in history.)[14] In 1798, he was appointed a judge of the Tennessee Supreme Court, serving until 1804.[15]

In addition to his legal and political career, Jackson prospered as planter, slave owner, and merchant. He built a home and the first general store in Gallatin, Tennessee in 1803. The next year he acquired the Hermitage, a 640-acre (259 ha) plantation in Davidson County, near Nashville. Jackson later added 360 acres (146 ha) to the plantation, which eventually grew to 1,050 acres (425 ha). The primary crop was cotton, grown by enslaved workers. Starting with nine slaves, Jackson held as many as 44 by 1820, and later held up to 150 slaves, making him among the planter elite. Throughout his lifetime Jackson may have owned as many as 300 slaves.[16][17]

Jackson was a major land speculator in West Tennessee after he had negotiated the sale of the land from the Chickasaw Nation in 1818 (termed the Jackson Purchase). He was one of the three original investors who founded Memphis, Tennessee in 1819 (see History of Memphis, Tennessee).[18]

Military career

War of 1812

Main articles: Creek War and Battle of New Orleans

Jackson was appointed commander of the Tennessee militia in 1801, with the rank of colonel. He was later elected major general of the Tennessee militia in 1802.[19]

During the War of 1812, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh encouraged the "Red Stick" Creek Indians of northern Alabama and Georgia to attack white settlements. He had unified tribes in theNorthwest to rise up against the Americans, trying to repel European American settlers from those lands north of the Ohio. Four hundred settlers were killed in the Fort Mims massacre. In the resulting Creek War, Jackson commanded the American forces, which included Tennessee militia, U.S. regulars, and Cherokee, Choctaw, and Lower Creek warriors. Sam Houston and David Crockett served under Jackson in this campaign.

Jackson defeated the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. US forces and their allies killed 800 Red Stick warriors in this battle, but Jackson spared the chief Red Eagle, a mixed-race man also known as William Weatherford. After the victory, Jackson imposed the Treaty of Fort Jackson upon both the Upper Creek enemies and the Lower Creek allies, wresting twenty million acres (81,000 km²) in present-day Georgia and Alabama from all the Creek for European-American settlement. Jackson was appointed Major General after this action.

According to author Gloria Jahoda, the Creeks coined their own name for him, Jacksa Chula Harjo "Jackson, old and fierce".[20]

Jackson's service in the War of 1812 against the United Kingdom was conspicuous for bravery and success. When British forces threatened New Orleans, Jackson took command of the defenses, including militia from several western states and territories. He was a strict officer but was popular with his troops. They said he was "tough as old hickory" wood on the battlefield, and he acquired the nickname of "Old Hickory". In the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, Jackson's 5,000 soldiers won a decisive victory over 7,500 British. At the end of the battle, the British had 2,037 casualties: 291 dead (including three senior generals), 1,262 wounded, and 484 captured or missing. The Americans had 71 casualties: 13 dead, 39 wounded, and 19 missing.[21]

Constitutional Crisis

Jackson ordered the arrest of U. S. District Court Judge Dominick Hall in March, 1815, after the judge signed a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of a Louisiana legislator that Jackson had arrested.[22] Louis Louaillier had written an anonymous piece in the New Orleans newspaper, challenging Jackson's refusal to release the militia, after the British ceded the field of battle.[23]Jackson had claimed the authority to declare martial law over the entire City of New Orleans, not merely his "camp."[24] After ordering the arrest of a Louisiana legislator, a federal judge, a lawyer and after intervention of Joshua Lewis, a State Judge, who was simultaneously serving under Jackson in the militia, and who also signed a writ of habeas corpus against Jackson, his commanding officer, seeking Judge Hall's release, Jackson relented.[25]

Civilian authorities in New Orleans had reason to fear Jackson. But they fared better than did the six members of the militia whose executions, ordered by Jackson, would surface as the Coffin Handbills during his 1828 Presidential campaign. Nonetheless, Jackson became a national hero for his actions in this battle and the War of 1812.[26] By a resolution on February 27, 1815, Jackson received the Thanks of Congress as well as a Congressional Gold Medal.[27] Alexis de Tocqueville, "underwhelmed" by Jackson, later commented in Democracy in America that Jackson "...was raised to the Presidency, and has been maintained there, solely by the recollection of a victory which he gained, twenty years ago, under the walls of New Orleans."[28]

First Seminole War

Main article: Seminole Wars

Jackson served in the military again during the First Seminole War. He was ordered by President James Monroe in December 1817 to lead a campaign in Georgia against the Seminoleand Creek Indians. Jackson was also charged with preventing Spanish Florida from becoming a refuge for runaway slaves. Critics later alleged that Jackson exceeded orders in his Florida actions. His directions were to "terminate the conflict".[29] Jackson believed the best way to do this was to seize Florida. Before going, Jackson wrote to Monroe, "Let it be signified to me through any channel ... that the possession of the Floridas would be desirable to the United States, and in sixty days it will be accomplished."[30] Monroe gave Jackson orders that were purposely ambiguous, sufficient for international denials.

The Seminole attacked Jackson's Tennessee volunteers. The Seminole attack left their villages vulnerable, and Jackson burned their houses and the crops. He found letters that indicated that the Spanish and British were secretly assisting the Indians. Jackson believed that the United States could not be secure as long as Spain and the United Kingdom encouraged Indians to fight, and argued that his actions were undertaken in self-defense. Jackson captured Pensacola, Florida, with little more than some warning shots, and deposed the Spanish governor. He captured and then tried and executed two British subjects, Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot, who had been supplying and advising the Indians. Jackson's actions struck fear into the Seminole tribes as word spread of his ruthlessness in battle (he became known as "Sharp Knife").

The executions, and Jackson's invasion of territory belonging to Spain, a country with which the U.S. was not at war, created an international incident. Many in the Monroe administration called for Jackson to be censured. The Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, an early believer in Manifest Destiny, defended Jackson. When the Spanish minister demanded a "suitable punishment" for Jackson, Adams wrote back, "Spain must immediately [decide] either to place a force in Florida adequate at once to the protection of her territory ... or cede to the United States a province, of which she retains nothing but the nominal possession, but which is, in fact ... a post of annoyance to them."[31] Adams used Jackson's conquest, and Spain's own weakness, to get Spain to cede Florida to the United States by the Adams–Onís Treaty. Jackson was subsequently named Florida's military governor and served from March 10, 1821, to December 31, 1821.

Election of 1824

Main article: United States presidential election, 1824

The Tennessee legislature nominated Jackson for President in 1822. It also elected him U.S. Senator again. By 1824, the Democratic-Republican Party had become the only functioning national party. Its Presidential candidates had been chosen by an informal Congressional nominating caucus, but this had become unpopular. In 1824, most of the Democratic-Republicans in Congress boycotted the caucus. Those who attended backed Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford for President and Albert Gallatin for Vice President. A Pennsylvania convention nominated Jackson for President a month later, stating that the irregular caucus ignored the "voice of the people" and was a "vain hope that the American people might be thus deceived into a belief that he [Crawford] was the regular democratic candidate".[32] Gallatin criticized Jackson as "an honest man and the idol of the worshippers of military glory, but from incapacity, military habits, and habitual disregard of laws and constitutional provisions, altogether unfit for the office".[33]

Besides Jackson and Crawford, the Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and House Speaker Henry Clay were also candidates. Jackson received the most popular votes (but not a majority, and four states had no popular ballot). The electoral votes were split four ways, with Jackson having a plurality. Because no candidate received a majority, the election was decided by the House of Representatives, which chose Adams. Jackson supporters denounced this result as a "corrupt bargain" because Clay gave his state's support to Adams, who subsequently appointed Clay as Secretary of State. As none of Kentucky's electors had initially voted for Adams, and Jackson had won the popular vote, some Kentucky politicians criticized Clay for violating the will of the people in return for personal political favors. Jackson's defeat burnished his political credentials, however; many voters believed the "man of the people" had been robbed by the "corrupt aristocrats of the East".

Election of 1828

Main article: United States presidential election, 1828

Jackson resigned from the Senate in October 1825, but continued his quest for the Presidency. The Tennessee legislature again nominated Jackson for President. Jackson attracted Vice PresidentJohn C. Calhoun, Martin Van Buren, and Thomas Ritchie into his camp (Van Buren and Ritchie were previous supporters of Crawford). Van Buren, with help from his friends in Philadelphia andRichmond, revived the old Republican Party, gave it a new name as the Democratic Party, "restored party rivalries", and forged a national organization of durability.[34] The Jackson coalition handily defeated Adams in 1828.

During the election, Jackson's opponents referred to him as a "jackass". Jackson liked the name and used the jackass as a symbol for a while, but it died out. However, it later became the symbol for the Democratic Party when cartoonist Thomas Nast popularized it.[35]

The campaign was very much a personal one. As was the custom at the time, neither candidate personally campaigned, but their political followers organized many campaign events. Both candidates were rhetorically attacked in the press, which reached a low point when the press accused Jackson's wife Rachel of bigamy. Though the accusation was true, as were most personal attacks leveled against him during the campaign, it was based on events that occurred many years prior (1791 to 1794). Jackson said he would forgive those who insulted him, but he would never forgive the ones who attacked his wife. Rachel died suddenly on December 22, 1828, before his inauguration, and was buried on Christmas Eve.

Inauguration

Main article: First inauguration of Andrew Jackson

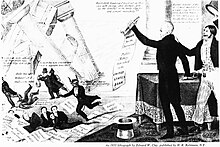

Jackson was the first President to invite the public to attend the White House ball honoring his first inauguration. Many poor people came to the inaugural ball in their homemade clothes. The crowd became so large that Jackson's guards could not keep them out of the White House, which became so crowded with people that dishes and decorative pieces inside were eventually broken. Some people stood on good chairs in muddied boots just to get a look at the President. The crowd had become so wild that the attendants poured punch in tubs and put it on the White House lawn to lure people outside. Jackson's raucous populism earned him the nickname "King Mob".

Election of 1832

Main article: United States presidential election, 1832

In the 1832 Presidential Election, Jackson faced opposition from Republican Henry Clay, who was a senator from Kentucky and former Speaker of the House, as well as Anti-Mason William Wirt, an attorney from Maryland.[36] For the first time in American history, all political parties nominated their candidates via a nominating convention.[37] Jackson easily won re-election, amassing 219 electoral votes, and 54.7% of the popular vote.[38] The Anti-Masonic Party used Northern sentiment against Freemasonry, which they asserted was infiltrating the federal government, to attack Jackson, who was a Mason.[39] John C. Calhoun, Vice President under John Quincy Adams and during part of Jackson's first term, had resigned over differences with Jackson, particularly over nullification and the Petticoat affair;[40] Jackson replaced him with longtime confidant Martin Van Buren of New York.[41]

The predominant issue in the 1832 election was the Bank War – a debate over whether or not to recharter the Second Bank of the United States.[42] Though the bank need not be rechartered until 1836 (its 20-year charter began in 1816),[43] bank president Nicholas Biddle and Clay, both political rivals of Jackson, sought to recharter the bank four years early. Clay hoped to "ride the probank [sic] bandwagon into the White House in 1832."[44] Clay was wrong, however, as Jackson's veto of the bank recharter furthered his persona as an advocate for the common man, and he won re-election.[45] Upon his re-election, Jackson held to his veto, and deposited federal monies in to state banks, which also helped him further a states' rights platform;[46] eventually, these deposits brought about a congressional censure.[42]

Presidency 1829–1837

See also: Jacksonian democracy

| The Jackson Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Andrew Jackson | 1829–1837 |

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | 1829–1832 |

| None | 1832–1833 | |

| Martin Van Buren | 1833–1837 | |

| Secretary of State | Martin Van Buren | 1829–1831 |

| Edward Livingston | 1831–1833 | |

| Louis McLane | 1833–1834 | |

| John Forsyth | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | Samuel D. Ingham | 1829–1831 |

| Louis McLane | 1831–1833 | |

| William J. Duane | 1833 | |

| Roger B. Taney | 1833–1834 | |

| Levi Woodbury | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of War | John H. Eaton | 1829–1831 |

| Lewis Cass | 1831–1836 | |

| Attorney General | John M. Berrien | 1829–1831 |

| Roger B. Taney | 1831–1833 | |

| Benjamin F. Butler | 1833–1837 | |

| Postmaster General | William T. Barry | 1829–1835 |

| Amos Kendall | 1835–1837 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | John Branch | 1829–1831 |

| Levi Woodbury | 1831–1834 | |

| Mahlon Dickerson | 1834–1837 | |

Federal debt

See also: Panic of 1837

In January 1835, Jackson paid off the entire national debt, the only time in U.S. history that has been accomplished.[47][48] However, this accomplishment was short lived. A severedepression from 1837 to 1844 caused the national debt to increase to over $3.3 million by January 1, 1838[49] and it has not been paid in full since.[50]

Electoral College

Jackson repeatedly called for the abolition of the Electoral College by constitutional amendment in his annual messages to Congress as President.[51][52] In his third annual message to Congress, he expressed the view "I have heretofore recommended amendments of the Federal Constitution giving the election of President and Vice-President to the people and limiting the service of the former to a single term. So important do I consider these changes in our fundamental law that I can not, in accordance with my sense of duty, omit to press them upon the consideration of a new Congress."[53]

Spoils system

Main article: Spoils system

When Jackson became President, he implemented the theory of rotation in office for political appointments, declaring it "a leading principle in the republican creed";[51] many of the individuals in government offices were holdovers from the Presidency of George Washington, whom Jackson thought were corrupt. He noted, "In a country where offices are created solely for the benefit of the people no one man has any more intrinsic right to official station than another."[54] He believed that rotation in office would prevent the development of a corrupt bureaucracy. Opposed to this view however, were Jackson's supporters who in order to strengthen party loyalty wanted to give the posts to other party members. In practice, this would have meant the continuation of the patronage system by replacing federal employees with friends or party loyalists.[55] By the end of his first four years, Jackson had dismissed nearly 20% of the Federal employees who were working at the start of his first term, replacing them with political appointees from his party. This resulted in the appointment of many functionaries who had no training or experience in the fields for which they were now responsible for administering.[56] While Jackson did not start the "spoils system", the political realities of Washington did in the end force him to encourage its growth despite personal reservations.[57]

Opposition to the National Bank

Main article: Bank War

See also: Banking in the Jacksonian Era

The Second Bank of the United States was authorized for a 20-year period during James Madison's tenure in 1816. In 1832, the issue materialized as part of a campaign strategy orchestrated by Henry Clay that ultimately failed, but signaled the end for the bank – four years before it was necessary, the bank applied for a recharter. Jackson vetoed the bill.[42] In Jackson's veto message, he conceded that a national bank may be "convenient", it is "subversive of the rights of the States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people." He went on to call the bank a "monopoly" that hindered the common man, whom he strived to represent as president.[58] Moreover, Jackson thought America should be an "agricultural republic", and that the bank hindered that notion, as it favored northeastern states over southern and western ones, and that it "improved the fortunes of commercial and industrial businesses at the expense of farmers and laborers."[59]

In 1833, Jackson removed federal deposits from the bank, whose money-lending functions were taken over by the legions of local and state banks that materialized across America, thus drastically increasing credit and speculation.[60] Three years later, Jackson issued the Specie Circular, an executive order that required buyers of government lands to pay in "specie" (gold or silver coins). The result was a great demand for specie, which many banks did not have enough of to exchange for their notes, causing the Panic of 1837, which threw the national economy into a deep depression. It took years for the economy to recover from the damage, however the bulk of the damage was blamed on Martin Van Buren, who took office in 1837.[61] Whitehouse.govnotes,

Basically the trouble was the 19th-century cyclical economy of "boom and bust," which was following its regular pattern, but Jackson's financial measures contributed to the crash. His destruction of the Second Bank of the United States had removed restrictions upon the inflationary practices of some state banks; wild speculation in lands, based on easy bank credit, had swept the West. To end this speculation, Jackson in 1836 had issued a Specie Circular requiring that lands be purchased with hard money--gold or silver. In 1837 the panic began. Hundreds of banks and businesses failed. Thousands lost their lands. For about five years the United States was wracked by the worst depression thus far in its history.—Whitehouse.gov official biography of Martin Van Buren[62]

The U.S. Senate censured Jackson on March 28, 1834, for his action in removing U.S. funds from the Bank of the United States.[63] The censure was a political maneuver spearheaded by Jackson-rival Senator Henry Clay, which served only to perpetuate the animosity between he and Jackson.[42] During the proceedings preceding the censure, Jackson called Clay "reckless and as full of fury as a drunken man in a brothel", and the issue was highly divisive within the Senate, however the censure was approved 26–20 on March 28.[42] When the Jacksonians had a majority in the Senate, the censure was expunged after years of effort by Jackson supporters, led by Thomas Hart Benton, who though he had once shot Jackson in a street fight, eventually became an ardent supporter of the president.[42][64]

No comments:

Post a Comment